Abstract

A stray female cat of unknown age, presenting bright red watery diarrhea, was submitted to the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency for diagnosis. In the small intestines extracted from the necropsied cat, numerous white oval-shaped organisms were firmly embedded in the mucosa and there was thickening of intestinal wall. Histopathological analysis revealed severe necrotizing enteritis, together with atrophied intestinal villi, exfoliated enterocytes, and parasitic worms. Recovered worms were identified as Pharyngostomum cordatum by morphological observation and genetic analysis. Although P. cordatum is known to occur widely in Korea, this is the first clinical description of an infection by P. cordatum causing severe feline enteritis.

-

Key words: Pharyngostomum cordatum, trematode, cat, diarrhea, Korea

INTRODUCTION

Enteritis in cats is caused by infectious agents (viruses, bacteria, and parasites), with parasites being the primary cause of diarrhea, especially among strays. Intestinal helminths (e.g., nematodes, trematodes, and cestodes) have been identified in the feline alimentary system [

1]. Within the trematodes, 26 species have been detected in cats in Korea: 10 species by 2000 [

2–

5], 15 species in 2005 [

6], and 1 species in 2009 [

7]. The intestinal trematode

Neodiplostomum seoulense (formerly

Fibricola seoulensis), which is closely related to

Pharyngostomum cordatum (Digenea: Diplostomidae), causes serious diarrhea and enteritis in human and laboratory animals, including rats and mice [

8]. The snake,

Rhabdophis tigrina, serves as a second intermediate host of these 2 species of trematode [

9].

P. cordatum infects carnivorous mammals worldwide. Domestic and wild cats act as the definitive hosts of this fluke, whose adults parasitize the small intestines of cats. The intermediate hosts, from which the parasite infects cats, are tadpoles, frogs, and frog-eating animals, including certain snakes [

10]. Infection by this fluke in cats has been widely reported in Germany, Romania, China, Japan, and India [

11–

15]. In the Republic of Korea (Korea),

P. cordatum was first recovered in the small intestines of cats from Seoul [

16]. The prevalence of this fluke in cats in Korea has been reported [

6,

17]. However, no studies have described the pathology of

P. cordatum infection in domestic felines. Here, we present the first clinical case of necrotizing enteritis caused by this fluke in a stray cat in Korea.

CASE RECORD

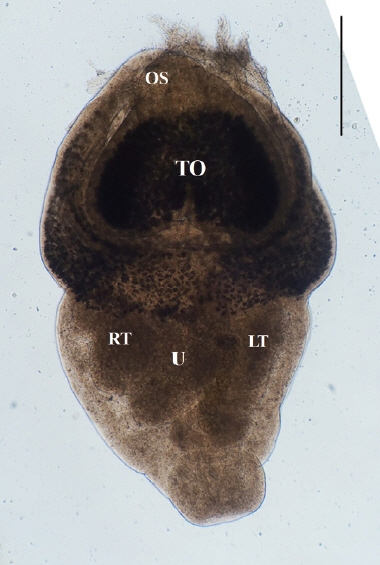

In December 2017, a stray female cat was found dead on the street and submitted to the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency for diagnostic examination. Clinical signs and individual information such as breed and age were unavailable. Bright red watery diarrhea was observed around the anus. Upon dissection, the small intestinal wall was observed to have thickened, with congested and edematous mucosa. Macroscopic examination revealed numerous white organisms that had attached deep in the mucosa of the duodenum and jejunum (

Fig. 1). These organisms were 0.1–0.2 cm in length and round or oval.

After necropsy, representative tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hr and routinely processed. Processed tissues were embedded in paraffin, then stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

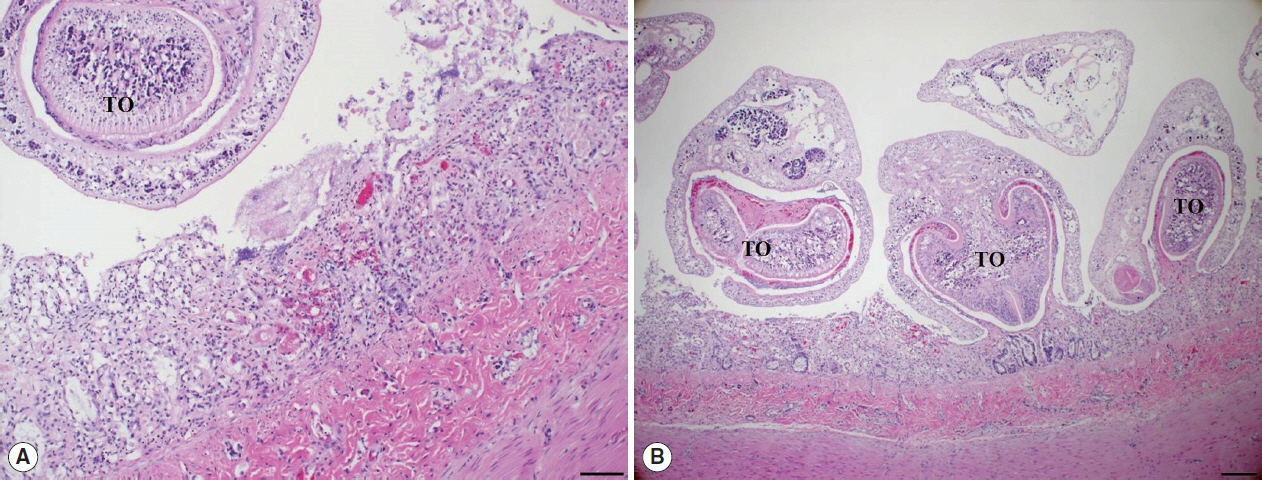

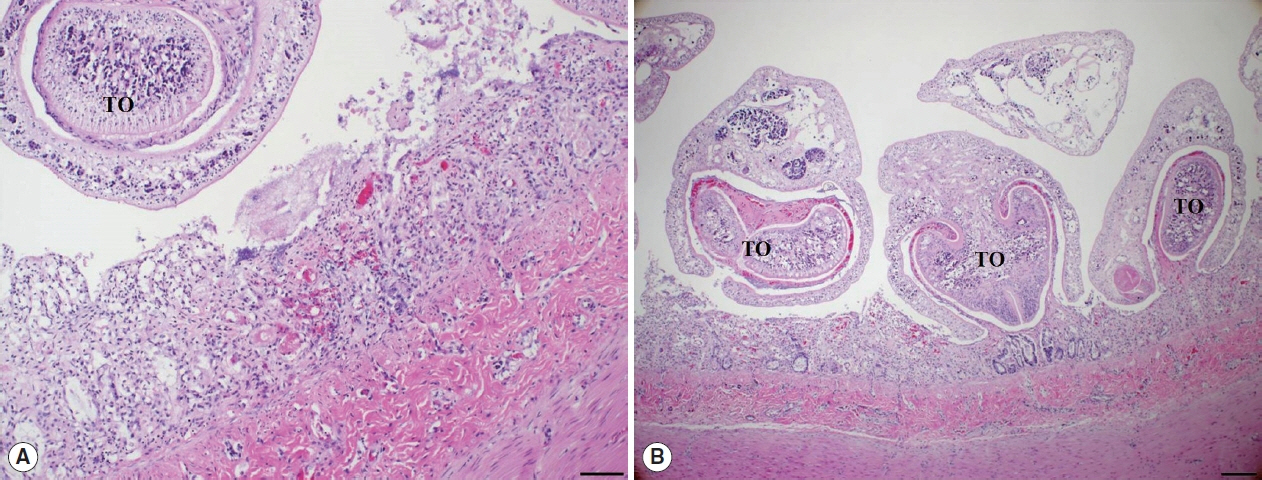

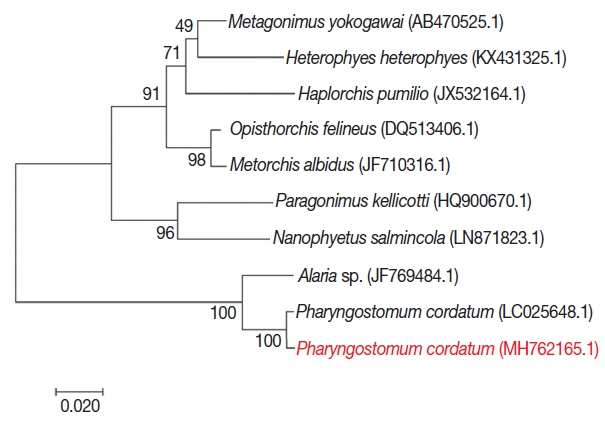

Histopathological examination of the small intestine revealed severe necrotizing enteritis, with atrophied small intestinal villi and enterocyte exfoliation (

Fig. 2A). Moreover, intestinal crypt epithelial cells were degenerated or necrotized. In the lamina propria, numerous lymphocytes and a few macrophages were infiltrated. Several trematodes were present within the intestinal lesions, having embedded themselves among the villi and pulling bits of mucosa into the anterior spoon-shaped region of their bodies (

Fig. 2B). No other organ presented histopathological lesions.

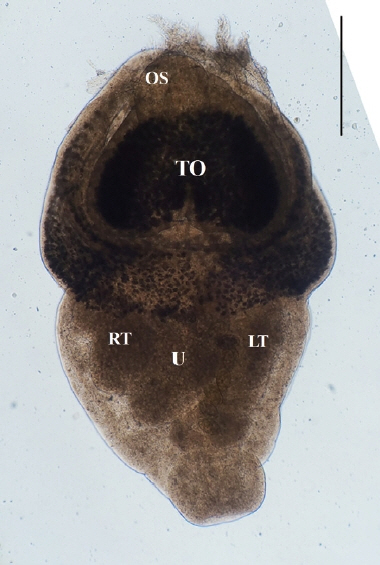

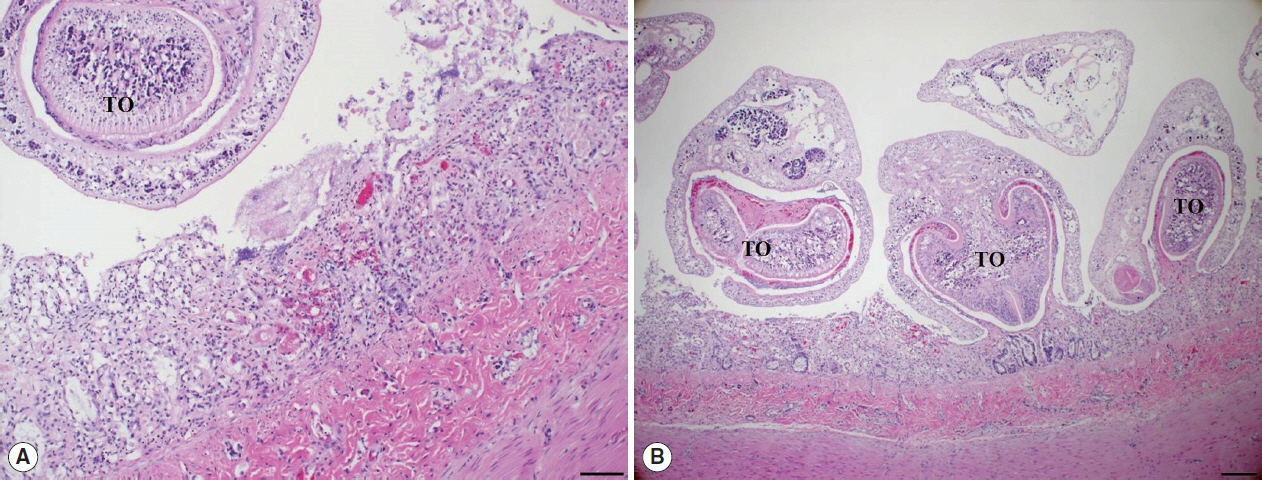

Direct microscopy and PCR were employed to identify the parasitic species. Worms collected from intestines were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin under cover glass pressure and identified using microscopy (

Fig. 3). Body shape was stout, fleshed, and indistinctly bipartite. Body dimensions were as follows: length 1.77 mm, maximum width at anterior body 1.13 mm, minimum width at hind body 0.38 mm. A small and subterminal oral sucker was located at the end of anterior body. A huge and cordiform tribocytic organ occupied almost the entire anterior body. Two slightly lobulated testes and a coiled uterus were adjacent in the posterior body.

Genomic DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded blocks of small intestine using a QIAamp DNA FFPF Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following manufacturer protocol. Partial and complete sequences of 5.8 Sribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene, internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2), 28S rRNA gene (GenBank accession number: LC025648.1) were PCR amplified using the following primers: 5′-TGTCGATGAAGAG TGCAGCCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATCAGTTACATTGCCACATGC-3′ (reverse). Thermocycling conditions were as follows: 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The PCR product was purified using a QIA amp Purification kit (Qiagen) and commercially sequenced (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea).

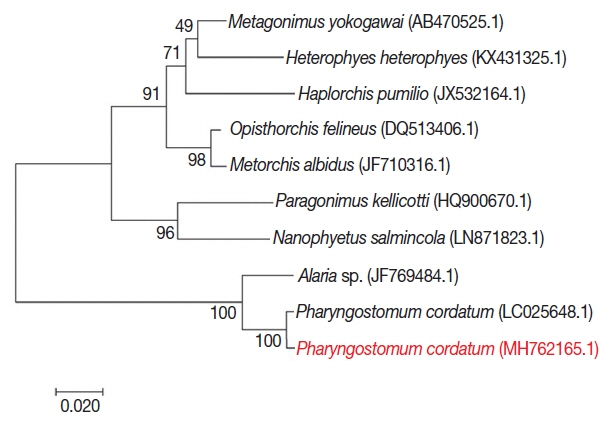

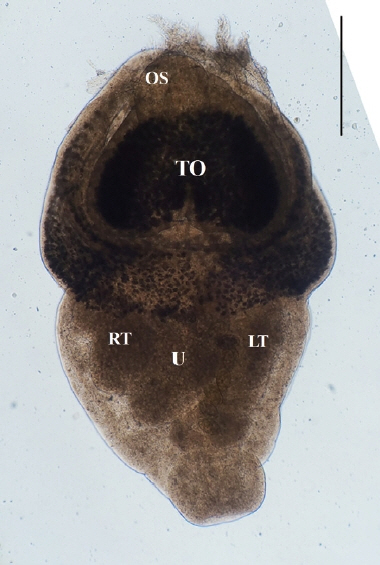

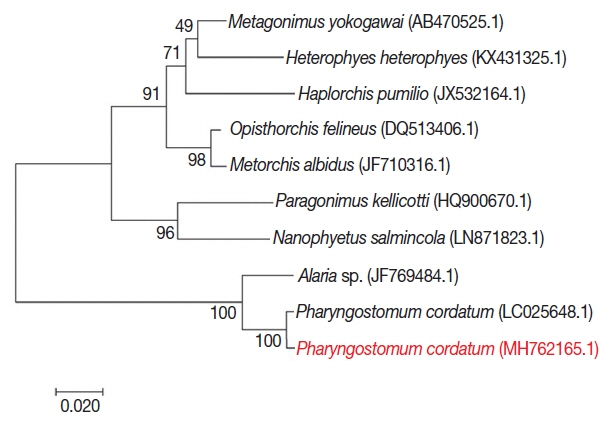

For phylogenetic analysis, sequences were aligned in BioEdit (ver. 7.2.6; Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, California, USA) and then analyzed in MEGA7 (Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania, USA). Intestinal flukes (

Alaria sp.,

Haplorchis pumilio, Heterophyes heterophyes, Metagonimus yokogawai, and

Nanophyetus salmincola), a lung fluke (

Paragonimus kellicotti), and a liver fluke (

Opisthorchis felineus) were used as outgroups. The sequence in this study (GenBank accession number: MH762165.1) showed high identity with

Pharyngostomum cordatum (99%) and

Alaria sp. (94%) (

Fig. 4). The trematode was closely related to the other intestinal flukes, and to the lung and liver fluke. All of these parasites are commonly found in cats. Screening with bacterial isolation and PCR failed to uncover any enterotropic bacterial and viral infections including feline parvovirus and feline coronavirus. To detect viral nucleic acid, commercial PCR/RT-PCR kit were used (iNtRON, Seoul, Korea).

DISCUSSION

In this study, histopathological changes of the intestinal mucosa associated with P. cordatum infection were observed. The animal exhibited severe diarrhea and necrotizing enteritis, especially in the duodenum and jejunum. Fluke attachment and damage of intestinal mucosa are the primary causes of these pathological lesions, by initiating inflammatory reactions that then result in mucosal necrosis and hemorrhage. The oral suckers of flukes probably induce local irritation, erosion, and ulceration.

Intestinal fluke infestations in cats can either be asymptomatic or cause abdominal pain, appetite loss, weakness, and diarrhea. Although the main clinical sign of

P. cordatum-infected cats is chronic diarrhea, this symptom is often absent in affected animals [

18]. In a previous report, for example, only 1 of 4 infected cats developed diarrhea, whereas the remainder showed no clinical abnormalities [

18]. In this case, we did not have access to exact clinical symptoms because the cat was found after death. Although viruses and bacteria are also capable of causing diarrhea in cats, and the enteritis presented in this case study is similar to parvoviral enteritis, screening did not detect any viral or bacterial presence. We concluded that the pathology observed in the dead cat originated from

P. cordatum infection, as it was the only etiological agent identified.

Human and veterinary clinics typically diagnose

P. cordatum infection through detecting eggs in fecal examinations [

18]. Thus, the morphology of the egg and adult is already known [

16,

19]. Although we could not obtain fecal samples, we identified adult parasites in the small intestine using direct microscopy and PCR. The morphological characteristics we recorded for

P. cordatum from microscopic analysis are consistent with previous description [

16]. Moreover, our successful PCR identification of this parasite suggests that molecular techniques would enable rapid diagnosis of

P. cordatum infection in domestic and wild cats, whether from fecal or tissue samples.

Since the first report of

P. cordatum infection in 1981, multiple surveys on intestinal trematode prevalence in the stray cats of Korea have been conducted. The parasite has been detected in 63/438 (14.4%) feral cats from Busan [

6] and 3/41 (7.3%) feral cats from Seoul [

5]. Thus,

P. cordatum infection is an endemic feline disease in Korea, and the parasite should be considered one of the most important for cats. We recommend that veterinarians take care to distinguish

P. cordatum infection from other causes of enteric disease in cats of Korea.

Stray cats can act as reservoirs, carriers, transmitters, and definitive hosts for many intestinal parasites, including those that are potentially zoonotic. Although no known cases of

P. cordatum infection in humans have been reported, we cannot exclude the possibility of

P. cordatum zoonosis [

19]. Thus, continuous monitoring of intestinal parasites in stray cats is necessary to allow for early diagnosis and control measures in domestic animals and wildlife of Korea.

Notes

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We have no conflict of interest related to this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported financially by a grant (N-1543069-2015-99-01) from the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, Republic of Korea.

Fig. 1Gross findings. White organisms observed in the mucosa of the small intestine.

Fig. 2Histopathological findings. (A) The villous atrophy, exfoliation of enterocytes, and a sectioned worm with the tribocytic organ (TO) were noticed in the lesion of small intestine. H&E, Bar=100 μm. (B) Several trematodes with the TO were characteristically attached in the intestinal mucosa of cat. H&E, Bar=200 μm.

Fig. 3An unstained P. cordatum adult collected from small intestine of stray cat. Scale bar=500 μm. OS, oral sucker; TO, tribocytic organ; U, uterus; RT, right testis; LT, left testis.

Fig. 4Phylogenetic tree of P. cordatum. Phylogenetic tree showing relationship of P. cordatum was drawn with 5.8S ribosomal RNA gene, internal transcribed spacer 2, 28S rRNA gene, partial and complete sequence. GenBank accession number.

References

- 1. Chai JY, Bahk YY, Sohn WM. Trematodes recovered in the small intestine of stray cats in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2013;51:99-106.

- 2. Kang HJ. Studies on the parasitic helminths of the cats in western province of Kyung Sang Nam-do. Res Bull Chinju Agric Coll 1967;6:91-96. (in Korean).

- 3. Lee HS. A survey on helminth parasites of cats in Gyeongbuk Area. Korean J Vet Res 1979;19:57-61.

- 4. Eom KS, Son SY, Lee JS, Rim HJ. Heterophyid trematodes (Heterophyopsis continua, Pygidiopsis summa and Heterophyes heterophyesnocens) from domestic cats in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1985;23:197-202. (in Korean).

- 5. Huh S, Sohn WM, Chai JY. Intestinal parasites of cats purchased in Seoul. Korean J Parasitol 1993;31:371-373.

- 6. Sohn WM, Chai JY. Infection status with helminthes in feral cats purchased from a market in Busan, Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2005;43:93-100.

- 7. Shin EH, Park JH, Guk SM, Kim JL, Chai JY. Intestinal helminth infections in feral cats and a raccoon dog on Aphaedo Island, Shinan-gun, with special notes on Gymnophalloides seoi infection in cats. Korean J Parasitol 2009;47:189-191.

- 8. Huh S, Chai JY, Hong ST, Lee SH. Clinical and histopathological findings in mice heavily infected with Fibricola seoulensis

. Korean J Parasitol 1988;26:45-53.

- 9. Chai JY, Sohn WM, Chung HL, Hong ST, Lee SH. Metacercariae of Pharyngostomum cordatum found from the European grass snake, Rhabdophis tigrina, and its experimental infection to cats. Korean J Parasitol 1990;28:175-181.

- 10. Wallace FG. The life cycle of Pharyngostomum cordatum (Diesing) Ciurea (Trematoda: Alariidae). Trans Am Microscop Soc 1939;58:49-61.

- 11. Diesing CM. Systema Helminthus. Vienna, Austria. Vindobonae. Braumüller; 1851.

- 12. Ciurea I. Sur quelque trematodes du renard et du chat sauvage. Compt Rend Soc de Biol 1922;87:268-269.

- 13. Chen HT. Helminths of cats in Fukien and Kwangtung provinces with a list of those recorded from China. Lingnan Sci 1934;13:261-273.

- 14. Faust EC. Studies on Asiatic holostomes (Class Trematoda). Rec Ind Mus 1927;29:215-227.

- 15. Dubey JP.

Pharyngostomum cordatum from the domestic cat (Felis catus) in India. J Parasitol 1970;56:194-195.

- 16. Cho SY, Lee JB.

Pharyngostomum cordatum (Trematoda: Alariidae) collected from a cat in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1981;19:173-174.

- 17. Huh S, Chai JY, Lee SH. Infection status of intestinal parasites in cats purchased in Seoul. Korean J Parasitol 1988;26:315.

- 18. To M, Okuma H, Ishida Y, Imai S, Ishii T. Fecundity of Pharyngostomum cordatum parasitic in domestic cats. J Vet Med Sci 1988;50:908-912.

- 19. Shin EH, Chai JY, Lee SH. Extraintestinal migration of Pharyngostomum cordatum metacercariae in experimental rodents. J Helminthol 2001;75:285-290.