Abstract

Neutrophils are important effector cells against protozoan extracellular parasite Entamoeba histolytica, which causes amoebic colitis and liver abscess in human beings. Apoptotic cell death of neutrophils is an important event in the resolution of inflammation and parasite's survival in vivo. This study was undertaken to investigate the ultrastructural aspects of apoptotic cells during neutrophil death triggered by Entamoeba histolytica. Isolated human neutrophils from the peripheral blood were incubated with or without live trophozoites of E. histolytica and examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Neutrophils incubated with E. histolytica were observed to show apoptotic characteristics, such as compaction of the nuclear chromatin and swelling of the nuclear envelop. In contrast, neutrophils incubated in the absence of the amoeba had many protrusions of irregular cell surfaces and heterogenous nuclear chromatin. Therefore, it is suggested that Entamoeba-induced neutrophil apoptosis contribute to prevent unwanted tissue inflammation and damage in the amoeba-invaded lesions in vivo.

-

Key words: Entamoeba histolytica, neutrophils, transmission electron microscopy, apoptosis, inflammation

Entamoeba histolytica causes amoebic dysentery and amoebic liver abscesses (

Stanley, 2003). Fifty million cases of invasive amebiasis and 100,000 deaths worldwide are estimated to occur annually (

Petri et al., 2002). Upon invasion, it may lyse various host cells including colonic epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and also cellular effector cells of the defense system (

Berninghausen and Leippe, 1997). Recently, it has also been demonstrated that

E. histolytica-induced host cell apoptosis occurs through caspase-dependent mechanism (

Huston et al., 2000). Neutrophils are the short-lived primary effector cells in host defense against injury and infection, and the activation of neutrophils is an important amoebicidal factor (

Seydel et al., 1997;

Ghosh et al., 2000;

Jarilo-Luna et al., 2002). Upon activation, neutrophils secrete a variety of molecules, such as reactive oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes, which can kill invading microorganisms, and cause substantial local tissue damage (

Takazoe K et al., 2000). Thus, neutrophil apoptosis plays a key role in the resolution of inflammation (

Savill, 1997). The typical morphological features of apoptosis include cell shrinkage, budding, DNA degradation to form a characteristic ladder when analyzed by electrophoresis, and its ultrastructural characteristics include chromatin condensation, shrinkage and fragmentation of nuclei, the formation of micronuclei and apoptotic bodies, condensation of cytoplasm, and blebs from the cell surface (

Vaux, 1993;

Vermes and Haanen, 1994;

Guejes et al., 2003). However, the ultrastructural changes or features of apoptotic neutrophils during cell death caused by

E. histolytica have not been previously investigated.

E. histolytica trophozoites (strain HM1:IMSS) were maintained axenically in TYI-S-33 medium at 37℃. During the late logarithmic phase, trophozoites were harvested by centrifugation at 200 g at 4℃ for 5 min after being chilled in an ice bath for 10 min and suspended in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with NaHCO3 2 g/L, gentamycin 50 mg/L, human serum albumin 1 g/L and 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FCS. Peripheral blood neutrophils were isolated from healthy donors. Briefly, heparinized blood was collected and diluted with piperazine-N, N'-bis (2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES) buffer containing 25 mM PIPES, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 25 mM NaOH, and 5.4 mM glucose (pH 7.4) at a 1:1 ratio. The diluted blood was then carefully overlaid on Histopaque (Histopaque 1083; Sigma Chemical Company) and centrifuged at 1,000 g at 4℃ for 30 min. Isolated fractions were cleared of erythrocytes by fast lysis with ice-cold distilled water. Neutrophils isolated by this procedure were more than 95% pure. Immediately following the isolation procedure, neutrophils (2 × 106/well) were incubated with culture medium at 37℃ for 15, 30 or 60 min in a humidified CO2 incubator (5% CO2, 95% air) with or without E. histolytica trophozoites (2 × 105/well) in 24 well tissue culture plates. After washing with PBS, portions of neutrophil sediments were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) overnight and then washed with the same buffer. They were then postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer at 4℃ for 1 hr and dehydrated. After dehydration, the cells were embedded in Epon 812, ultrathin sections were prepared by using an LKB-V ultramicrotome, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined under a transmission electron microscope (JEOL 100CX-II).

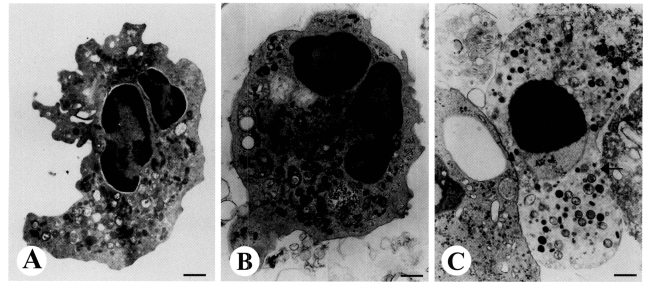

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed the ultrastructural alterations of cells undergoing apoptosis in human neutrophils incubated with

E. histolytica. Healthy neutrophils have irregular cell surfaces, polysegmented nuclei, and heterogenous nuclear chromatin without swelling of the nuclear envelope (

Fig. 1A). Following incubation with

E. histolytica for 15 min, the shapes of neutrophils became round with slight condensation of chromatin and cytoplasm (

Fig. 1B). Furthermore, after 30 min of incubation, neutrophils in close contact with a trophozoites showed apoptotic appearance, as evidenced by marked condensation of nuclear chromatin and swelling of the nuclear envelope (

Fig. 1C). After 60 min of incubation with

E. histolytica, neutrophils were found be necrotic morphology such as disruption of plasma membranes, cytoplasmic vacuolation, and loss of cellular contents (data not shown).

It has been known that the majority of dying cells after contact with

E. histolytica show a combination of apoptotic and necrotic morphology in vitro (

Ragland et al., 1994), although only a small percentage of cells had a necrotic or apoptotic appearance exclusively. Apoptotic cell death of human neutrophils induced by

E. histolytica is considered to be a important mechanism to lessen neutrophil-mediated tissue inflammation and damage in the parasite-infected lesions, because apoptotic cells can then be recognized and phagocytosed by macrophages in a non-phlogistic manner: that is, there is no release of pro-inflammatory mediators but a release of potential anti-inflammatory mediators such as transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and interleukin 10 (IL-10) (

Simon, 2003). Therefore, these observation led us to support universal finding that amoebae cause little or minimal inflammatory responses despite of extensive tissue lytic necrosis during liver invasion of

E. histolytica. In contrast, when cells become necrotic they have the potential to cause tissue injury and because of the release of proinflammatory mediators will amplify the inflammatory process. Following phagocytosis of necrotic cells, macrophages liberate pro-inflammatory mediators such as thromboxane B

2 (TxB

2), IL-8 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α). Therefore, it should be investigated how

E. histolytica can induce apoptosis and/or necrosis in immune cells to unravel complex milieu of inflammation in the parasite-infected lesions during amoebiasis in human beings.

Notes

-

This study was supported by Anti-Communicable Disease Control Program of the National Institute of Health Korea and National Research and Development Program, Korean Government (NIH 348-6111-215).

References

- 1. Berninghausen O, Leippe M. Necrosis versus apoptosis as the mechanism of target cell death induced by Entamoeba histolytica. Infect Immun 1997;65:3615-3621.

- 2. Ghosh PK, Ventura GJ, Gupta S, Serrano J, Tsutsumi V, Ortiz-Ortiz L. Experimental amebiasis: immunohistochemical study of immune cell populations. J Eukaryot Microbiol 2000;47:395-399.

- 3. Guejes L, Zurgil N, Deutsch M, Gilburd B, Shoenfeld Y. The influence of different cultivating conditions on polymorphonuclear leukocyte apoptotic processes in vitro, I: the morphological characteristics of PMN spontaneous apoptosis. Ultrastruct Pathol 2003;27:23-32.

- 4. Huston CD, Houpt ER, Mann BJ, Hahn CS, Petri WA. Caspase-dependent killing of host cells by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol 2000;2:617-625.

- 5. Jarilo-Luna RA, Campos-Rodriguez R, Tsutsumi V. Entamoeba histolytica: immunohistochemical study of hepatic amoebiasis in mouse. Neutrophils and nitric oxide as possible factors of resistance. Exp Parasitol 2002;101:40-56.

- 6. Petri WA, Haque R, Mann BJ. The bittersweet interface of parasite and host: Lectin-carbohydrate interactions during human invasion by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Annu Rev Microbiol 2002;56:39-64.

- 7. Ragland BD, Ashley LS, Vaux DL, Petri WA. Entamoeba histolytica: Target cells killed by trophozoites undergo DNA fragmentation which is not blocked by bcl-2. Exp Parasitol 1994;79:460-467.

- 8. Savill J. Apoptosis in resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 1997;61:375-380.

- 9. Seydel KB, Zhang T, Stanley SL. Neutrophils play a critical role in early resistance to amebic liver abscesses in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun 1997;65:3951-3953.

- 10. Simon HU. Neutrophil apoptosis pathways and theirmodifications in inflammation. Immunol Rev 2003;193:101-110.

- 11. Stanley SL. Amoebiasis. Lancet 2003;361:1025-1034.

- 12. Takazoe K, Tesch GH, Hill PA, et al. CD44-mediated neutrophil apoptosis in the rat. Kidney Int 2000;58:1920-1930.

- 13. Vaux DL. Toward an understanding of the molecular mechanisms of physiological cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:786-789.

- 14. Vermes I, Haanen C. Apoptosis and programmed cell death in health and disease. Adv Clin Chem 1994;31:177-246.

Fig. 1TEM view of apoptotic neutrophils induced by Entamoeba histolytica. Freshly isolated neutrophils (2 × 106/well) were incubated for 15, 30, or 60 min at 37℃ with or without E. histolytica (2 × 105/well) and then processed for TEM as described in the text. X 14,000. A. Neutrophils incubated for 30 min with medium alone contained nuclear lobes filled with heterochromatin. The cytoplasm was typical of normal neutrophil with numerous granules, mitochondria, and granular cytoplasmic matrix. B. Neutrophils incubated for 15 min with E. histolytica showed loss of irregular surface margins, and smooth outlines. Nuclei contained both eu- and hetero-chromatin. C. Neutrophils incubated for 30 min with E. histolytica contained a round nucleus filled with condensed chromatin, and the perinuclear space had widened (arrow). Bar = 1 µm.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Signaling Role of NADPH Oxidases in ROS-Dependent Host Cell Death Induced by Pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica

Young Ah Lee, Seobo Sim, Kyeong Ah Kim, Myeong Heon Shin

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2022; 60(3): 155. CrossRef - The state of art of neutrophil extracellular traps in protozoan and helminthic infections

César Díaz-Godínez, Julio C. Carrero

Bioscience Reports.2019;[Epub] CrossRef - Entamoeba histolytica Trophozoites Induce a Rapid Non-classical NETosis Mechanism Independent of NOX2-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species and PAD4 Activity

César Díaz-Godínez, Zayda Fonseca, Mario Néquiz, Juan P. Laclette, Carlos Rosales, Julio C. Carrero

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology.2018;[Epub] CrossRef - Entamoeba histolytica induces human neutrophils to form NETs

J. Ventura‐Juarez, MR. Campos‐Esparza, J. Pacheco‐Yepez, J. A López‐Blanco, A. Adabache‐Ortíz, M. Silva‐Briano, R. Campos‐Rodríguez

Parasite Immunology.2016; 38(8): 503. CrossRef - Modulatory mechanisms of enterocyte apoptosis by viral, bacterial and parasitic pathogens

Andre G Buret, Amol Bhargava

Critical Reviews in Microbiology.2014; 40(1): 1. CrossRef - Anoikis potential of Entameba histolytica secretory cysteine proteases: Evidence of contact independent host cell death

Sudeep Kumar, Rajdeep Banerjee, Nilay Nandi, Abul Hasan Sardar, Pradeep Das

Microbial Pathogenesis.2012; 52(1): 69. CrossRef - In vivo programmed cell death of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites in a hamster model of amoebic liver abscess

J. D. Villalba-Magdaleno, G. Perez-Ishiwara, J. Serrano-Luna, V. Tsutsumi, M. Shibayama

Microbiology.2011; 157(5): 1489. CrossRef - TGF‐β‐regulated tyrosine phosphatases induce lymphocyte apoptosis in Leishmania donovani‐infected hamsters

Rajdeep Banerjee, Sudeep Kumar, Abhik Sen, Ananda Mookerjee, Syamal Roy, Subrata Pal, Pradeep Das

Immunology & Cell Biology.2011; 89(3): 466. CrossRef - Involvement of Src Family Tyrosine Kinase in Apoptosis of Human Neutrophils Induced by Protozoan ParasiteEntamoeba histolytica

Seobo Sim, Jae-Ran Yu, Young Ah Lee, Myeong Heon Shin

The Korean Journal of Parasitology.2010; 48(4): 285. CrossRef - Calpain-dependent calpastatin cleavage regulates caspase-3 activation during apoptosis of Jurkat T cells induced by Entamoeba histolytica

Kyeong Ah Kim, Young Ah Lee, Myeong Heon Shin

International Journal for Parasitology.2007; 37(11): 1209. CrossRef - Involvement of β2-integrin in ROS-mediated neutrophil apoptosis induced by Entamoeba histolytica

Seobo Sim, Soon-Jung Park, Tai-Soon Yong, Kyung-Il Im, Myeong Heon Shin

Microbes and Infection.2007; 9(11): 1368. CrossRef - Trichomonas vaginalis promotes apoptosis of human neutrophils by activating caspase‐3 and reducing Mcl‐1 expression

J. H. KANG, H. O. SONG, J. S. RYU, M. H. SHIN, J. M. KIM, Y. S. CHO, J. F. ALDERETE, M. H. AHN, D. Y. MIN

Parasite Immunology.2006; 28(9): 439. CrossRef - Toxoplasma gondii Inhibits Apoptosis in Infected Cells by Caspase Inactivation and NF-κB Activation

Ji-Young Kim, Myoung-Hee Ahn, Hye-Sun Jun, Jai-Won Jung, Jae-Sook Ryu, Duk-Young Min

Yonsei Medical Journal.2006; 47(6): 862. CrossRef