Abstract

Although oncospheres of Taenia saginata asiatica can develop into cysticerci in immunodeficiency, immunosuppressed, and normal mice, no detailed information on the development features of these cysticerci from SCID mice is available. In the present study, the tumor-like cyst was found in the subcutaneous tissues of each of 10 SCID mice after 38-244 days inoculation with 39,000 oncospheres of T. s. asiatica. These cysts weighed 2.0-9.6 gm and were 1.5-4.3 cm in diameter. The number of cysticerci were collected from these cysts ranged from 125 to 1,794 and the cysticercus recovery rate from 0.3% to 4.6%. All cysticerci were viable with a diameter of 1-6 mm and 9 abnormal ones each with 2 evaginated protoscoleces were also found. The mean length and width of scolex, protoscolex, and bladder were 477 × 558, 756 × 727, and 1,586 × 1,615 µm, respectively. The diameters of suckers and rostellum were 220 µm and 70 µm, respectively. All cysticerci had two rows of rostellar hooks. These findings suggest that the SCID mouse model can be employed as a tool for long-term maintenance of the biological materials for advanced studies of immunodiagnosis, vaccine development, and evaluation of cestocidal drugs which would be most benefit for the good health of the livestocks.

-

Key words: cysticerci, SCID mice, Taenia saginata asiatica

INTRODUCTION

In many countries of East Asia, some people are fond of eating raw or undercooked meat and viscera of domestic and wild animals. These eating habits are important in the transmission of taeniasis (

Fan et al., 1992b). Although meat and viscera are commonly eaten and Cysticercus cellulosae is frequently found, but

T. saginata rather than

T. solium is the dominant species (

Cho et al., 1967;

Huang et al., 1966;

Kosin et al., 1972;

Arambulo et al., 1976). In 1992, Eom and Rim proposed this causative agent as a new species of

T. asiatica. After considering the closeness of this parasite with the classical

T. saginata, we recently proposed this causative agent of taeniasis as a subspecies of

T. saginata and named

T. s. asiatica. The classical

T. saginata was renamed as

T. s. saginata (

Fan et al., 1995).

Cysticerci of

T. s. asiatica have been mostly recovered from the liver of pig, cattle, goat, monkey and wild boar (

Fan et al., 1987;

Chan et al., 1987). However, pig has been determined to be the favorable intermediate host of this new subspecies (

Fan et al., 1990). In addition, some cysticerci in the liver of these intermediate hosts can develop to be degenerated or calcified within one month (

Fan et al., 1995). Since this human taeniid cestode has a very high host-specificity, experimental infections can only be repeated in cattle or pigs and it is not easy to obtain information on the biological factors of these tapeworms. Therefore, the establishment of a model with small size animal should be beneficial to the understanding of their developmental biology, immunodiagnosis, pathology, vaccine development, and evaluation of taenicides. Recently, oncospheres of

T. s. asiatica and

T. solium have been reported to develop into cysticerci in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. The mature cysticerci in the subcutaneous tissues of the SCID mice remained viable five months after infection (

Ito et al., 1997a,

1997b). Moreover, we have succeeded in establishing a rodent model for study of taeniasis using immunosuppressed or normal mice (

Wang et al., 1999a) and infecting hamster with rodent-derived cysticerci to sexual mature worms of

T. solium (

Wang, 1999b). However, no detailed information on the morphological characteristics of

T. s. asiatica cysticerci from SCID mice is available. In the present study, we determined the long period of time for viable cysticerci of

T. s. asiatica in SCID mice and also studied the morphological aspects of this metacestode in the rodent model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Worm collection

Adult worm of T. s. asiatica were collected from infected aborigines at the mountanous areas of Tatung Disrict of Ilan Country, in Taiwan. BALB/c SCID mice were bought from Animal Center, National Taiwan University in Taipei City.

Egg collection and hatching

Eggs of

T. s. asiatica were collected from the last ten gravid proglottids of the tapeworm and kept in a refrigerator at 4℃. These eggs were hatched by the enzyme technigue. The detail procedures have been previously described by Wang et al. (

1997).

Ten SCID mice were inoculated subcutaneously each with 39,000 oncospheres of T. s. asiatica. After experimental infection, the mice were kept in autoclaved (100℃ for 1 h) cages with "Beta-Chip" heat treated hardwood laboratory bedding (Northeaster Products Corp.) and covered with a filter cap. Food and drinking water were also autoclaved and provided ad libitum.

Count and measurement of T. s. asiatica cysticerci

All infected SCID mice were sacrificed after over anaesthesia of ether at various intervals (38-244 days) after infection. Cysticerci from the infected mice were collected, counted, and measured by the method described previously (

Fan et al., 1989).

RESULTS

Viable cysticerci recovery and weight and size of the tumor-like cyst

Between 38 and 244 days after inoculationg with 39,000 oncospheres of

T. s. asiatica into the subcutaneous tissues of each of 10 SCID mice, a tumor-like cyst was found in the inoculation site of each mouse. The mean weight and diameter of these transparent milky cysts were 4 (range: 1.5-9.6) gm and 3.2 (range: 1.5-4.3) cm, respectively. A total number of cysticerci were 5,899 collected from these cysts ranged from 125 to 1,794 and the mean cysticercus recovery rate of 1.5% and ranged from 0.3% to 4.6%. All cysticerci were viable with a mean diameter of 4 (1-6) mm. Among these cysticerci, 9 were found each with two evaginated protoscoleces in 3 SCID mice (

Table 1,

Fig. 1-18).

Table 2 shows the measurement and count of cysticerci from 6 infected SCID mice sacrificed from day 62 to day 215 after infection. The mean length and width of scolex, protoscolex, and bladder were 477 (205-1,090) × 558 (280-920), 756 (50-2,950) × 727 (50-2,165), and 1,586 (450-4,775) × 1,615 (425-4,240) µm, respectively. The diameters of suckers and rostellum were 220 (115-315) µm and 70 (30-115) µm, respectively. All the cysticerci had two row of rudimentary hooks. The large inner hooks were 16 (6-25) in number and 9 (3-18) µm long while the outer ones were too small and numerous. There were wart-like formation on the bladder surface (

Table 2,

Fig. 19-22).

DISCUSSION

T. solium,

T. s. asiatica, and

T. s. saginata may employ the pig as an intermediate host. After mature eggs are ingested by the intermediate host, oncospheres hatch from its membrane in the intestinal tract and penetrate the intestinal wall into blood vessels. Through the blood stream, oncospheres of

T. solium are carried to various muscles (

Beaver et al., 1984) and those of

T. s. asiatica and

T. s. saginata to the liver (

Fan et al., 1992b,

1996). They develop into cysticerci at these sites. Therefore, collection of cysticerci for experimental infection studies require pigs. Fortunately, Ito et al. (

1997a) recently succeeded in establishing a SCID mouse model for the development of cysticerci of

T. solium and

T. s. asiatica. This model has an advantage that the cysticerci of these two parasites remained viable five months after experimental infection. Moreover, we have demonstrated that cysticerci of

T. solium and

T. s. asiatica not only can develop in immunodeficient mice but also in immmunosuppressed mice and even in normal mice (

Wang et al., 1999a). We also found that C57 mice is the most suitable laboratory intermediate host for

T. solium among the immunosuppressed mice, since it has a high cysticercus recovery rate of 2.4%. In addition, normal C57 mice can also harbor cysticerci in their subcutaneous tissue, although the cysticercus recovery was relatively low (0.2%). In the establishment and maintenance of

T. solium or

T. s. asiatica cysticerci in immunosuppressed or normal mice, less efforts and costs are required (

Wang et al., 1999a).

In the present study, we found that cysticerci remained viable on day 244 after infection. These cysticerci had a large diameter of 4 (1-6) mm. Moreover, we obtained a high cysticercus recovery rate of 4.6% in a SCID mouse sacrificed on day 62. These findings indicate that the rodent model can be employed not only in the study of the developmental biology, immunodiagnosis, host-parasite relationship, and vaccine development, and of human taeniid cestodes but also can be used as a tool for long-term maintenance of the viable biological materials. In addition, the cysticerci in SCID mice in this study did not become calcified/degeneration after a long period of 244 days. This interval was much longer than that reported by Ito et al. (

1997a,

1997b).

T. s. asiatica cysticerci recovered from SCID mice in the present study were also much larger than those from pigs (

Fan et al., 1995). The increase in size of the cysticerci was found to be proportional to the days of infection. Although Ito et al. (

1997a,

1997b) reported that no rostallar hooks were observed on the scolex of cysticerci of

T. s. asiatica from SCID mice, we found that there were two rows of rudimentary hooks on the scolex of the cysticerci (

Fig. 21). The large inner hooks were 16 (range: 6-25) in mean number and 9 (range: 3-18) µm in length. These findings were similar to the cysticerci obtained from the pig's liver (

Fan et al., 1995). It has been suggested that the size of the cysticercus in the intermediate mammalian host might be controlled by some immune response which can not kill the established larvae (

Mitchell et al., 1977;

Lucas et al., 1980;

Ito, 1985;

Ishiwata et al., 1992;

Dixon and Jenkins, 1995). However, further studies are required to confirm these suggestions. Moreover, in our recent experimental study, we found that the normal and immunosuppressed mice (C3H, C57, and ICR strains) have been demonstrated to be useful as a tool for maintenance of the viable cysticerci of

T. solium and

T. s. asiatica living longer than one year (Wang et al., unpublished data).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to the National Science Council, Republic of China, for support of this research grant (NSC89-2320-B010-039) and a research grant (DOH89-DT-1022) by the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, ROC, and to Miss P. Huang and Miss C.W. Yen for their technical assistance.

References

- 1. Arambulo PV, Cabrera BD, Tongson MS. Studies on the zoonotic cycle of Taenia saginata taeniasis and cysticercosis in the Philippines. Int J Zoonoses 1976;3:77-104.

- 2. Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW. Clinical Parasitology. 1984, 9th Ed. Philadelphia. Lea & Febiger; pp 505-543.

- 3. Chan CH, Fan PC, Chung WC, Hsu MC, Chen YA. Studies of taeniasis in Taiwan. I. Prevalence of taeniasis among Atayal aborigines in Wulai District, Taipei County, North Taiwan. 1987. 1st Sino-USA Symposium on Parasitic Diseases. Sep 30-Oct 4, 1985; Taipei: 65-77.

- 4. Cho KM, Hong SO, Kim CH, et al. Studies on taeniasis on Cheju-Do. J Modern Med 1967;7:455-461.

- 5. Dixon JB, Jenkins P. Immunology of mammalian metacestode infections. I. Antigens, protective immunity and immunopathology. Helminthol Abstr 1995;64:533-542.

- 6. Eom KS, Rim HJ. Morphologic descriptions of Taenia asiatica sp. n. Korean J Parasitol 1993;31:1-6.

- 7. Fan PC, Chung WC, Chan CH, et al. Studies on taeniasis in Taiwan. III. Preliminary report on experimental infection of Taiwan Taenia in domestic animals. 1987. 1st Sino-USA Symposium on Parasitic Diseases. Sep 30-Oct 4, 1985; Taipei: 119-125.

- 8. Fan PC, Chung WC, Lin CY, Wu CC. Experimental infection of Taenia saginata (Poland strain) in Taiwanese pig. J Helminthol 1992b;66:198-204.

- 9. Fan PC, Chung WC, Lin CY, Wu CC, Soh CT. Experimental studies on Korea Taenia (Cheju strain) infection in domestic animals. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1989;83:395-403.

- 10. Fan PC, Chung WC, Soh CT, Kosaman ML. Eating habits of East Asian people and transmission of taeniasis. Acta Tropica 1992a;50:305-315.

- 11. Fan PC, Lin CY, Chen CC, Chung WC. Morphological description of Taenia saginata asiatica (Cyclophyllidea: Taeniidae) from man in Asia. J Helminthol 1995;69:299-303.

- 12. Fan PC, Lin CY, Chung WC, Wu CC. Experimental studies on the pathway for migration and the development of Taiwan Taenia in domestic pigs. Int J Parasitol 1996;25:45-48.

- 13. Fan PC, Soh CT, Kosin E. Pig as a favorable intermediate host of a possible new species of Taenia in Asia. Yonsei Rep Trop Med 1990;21:39-58.

- 14. Huang SW, Lin CY, Khaw OK. Studies on Taenia species prevalent among the aborigines in Wulai District, Taiwan. Part I. On the parasitological fauna of the aborigines in Wulai District. Bull Inst Zool, Academia Sinica, ROC 1966;5:87-91.

- 15. Ishiwata K, Oku Y, Ito M, Kamiya M. Responses to larval Taenia taeniaeformis in mice with severe combined immunodeficency (scid). Parasitology 1992;104:363-369.

- 16. Ito A. Thymus dependency of induced immune responses against Hymenolepis nana (cestode) using congenitally athymic nude mice. Clin Exp Immunol 1985;60:87-94.

- 17. Ito A, Chung WC, Chen CC, et al. Human Taenia eggs develop into cysticerci in scid mice. Parasitology 1997a;114:85-88.

- 18. Ito A, Ito M, Eom KS, et al. In vitro hatched oncospheres of Asian Taenia from Korea and Taiwan develop into cysticerci in the peritoneal of female scid (severe combined immunodeficiency) mice. Int J Parasitol 1997b;27:631-633.

- 19. Kosin E, Depary A, Djohansjah A. Taeniasis di pulau Samosir. Majalah Fakultas Kedokteran, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan 1972;3:5-11.

- 20. Lucas SB, Hassounah OA, Muller R, Doenhoff M. Abnormal development of Hymenolepis nana larvae in immunosuppressed mice. J Helminthol 1980;54:75-82.

- 21. Mitchell GF, Goding JW, Rickard MD. Studies on immune responses to larval cestodes in mice. Increased susceptibility of certain strains and hypothymic mice to Taenia taeniaeformis and analysis of passive transfer of resistance with serum. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci 1977;55:165-186.

- 22. Wang IC, Guo JX, Ma YX, Chung WC, Fan PC. Sexual development of Taenia solium in hamster from rodent-derived cysticerci. J Helminthol 1999b;73:347-350.

- 23. Wang IC, Ma XY, Guo JX, Chung WC, Lu SC, Fan PC. A comparative study on eggs hatching methods and oncospheres viability determination for eggs of Taenia solium (Henan strain). Int J Parasitol 1997;27:1311-1314.

- 24. Wang IC, Ma YX, Kuo CH, et al. Oncospheres of Taenia solium and Taenia saginata asiatica develop into metacestodes in normal and immunosuppressed mice. J Helminthol 1999a;73:183-186.

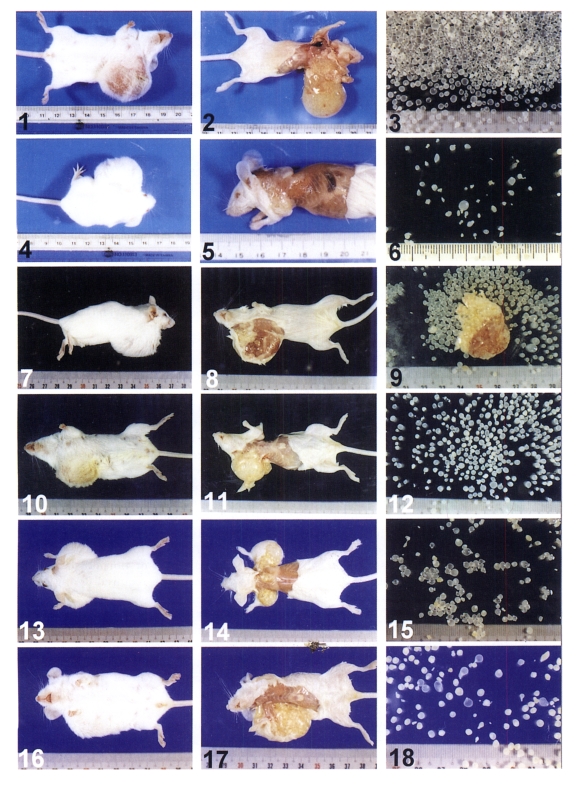

Figs. 1-18

Figs. 1-22. The viable metacestodes of Taenia saginata asiatica were found in big tumor-like cysts in 6 SCID mice 62-215 days after infection each with 39,000 oncospheres. Figs. 1-18. Numerous viable metacestodes were released from the big tumor-like cyst in six SCID mice after sacrifice and decortication.

1. A big tumor-like cyst (9.6 gm and 3 cm in diameter) occupied the left neck, thorax, and both front legs of the SCID mouse (No. 2).

2. Same as Fig. 1. The big tumor-like cyst was exposed after decortication.

3. Same as Fig. 1. Most of 1,794 viable cysticerci with a few evaginated ones released from the big tumor-like cyst.

4. A big tumor-like cyst (3.5 gm and 3 cm in diameter) occupied the left neck, thorax, and both front legs of the SCID mouse (No. 1).

5. Same as Fig. 4. The big tumor-like cyst was exposed after decortication.

6. Same as Fig. 4. A part of 125 viable cysticerci with a few evaginated ones released from the big tumor-like cyst.

7. A big tumor-like cyst (5.0 gm and 3.2 cm in diameter) occupied the right neck thorax, and a front leg of a SCID mouse (No. 4).

8. Same as Fig. 7. One large tumor-like cyst was observed after decortication.

9. Same as Fig. 7. More than half of 529 viable cysticerci and a big mass contained many ones released from the big tumor-like cyst.

10. A big tumor-like cyst (3 gm and 2.5 cm in diameter) occupied the right neck, thorax, and a front leg of a SCID mouse (No. 5).

11. Same as Fig. 10. One big tumor-like cyst was exposed after decortication.

12. Same as Fig. 10. Less than half of 649 viable cysticerci with a few evaginated ones released from the big tumor-like cyst.

13. A large and a small tumor-like cysts (1.5 and 2.5 gm and 1.5 and 2.5 cm in diameter) occupied both left and right thoraces and two front legs of the SCID mouse (No. 6).

14. Same as Fig. 13. A large (right) and a small (left) tumor-like cysts were observed after decortication.

15. Same as Fig. 13. About half of 323 viable cysticerci with a few evaginated ones released from the big tumor-like cyst.

16. A big tumor-like cyst (5.0 gm and 4.3 cm in length) occupied the right thorax, abdomen and two front legs of the SCID mouse (No. 7).

17. Same as Fig. 16. A big tumor-like cyst was exposed after decortication.

18. Same as Fig. 16. About one fourth of 557 viable cysticerci with a few evaginated ones released from the big tumor-like cyst.

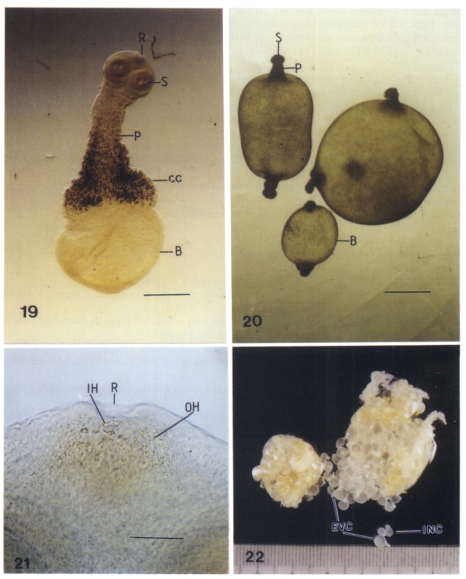

Abbreviations: B, bladder; CC, calcareous corpuscles; EVC, evaginated cysticercus; INC, invaginated cysticercus; IH, inner hooks; OH, outer hooks; P, protoscolex; R, rostellum; S, sucker.

Figs. 19-22

Figs. 1-22. The viable metacestodes of Taenia saginata asiatica were found in big tumor-like cysts in 6 SCID mice 62-215 days after infection each with 39,000 oncospheres. Figs. 19-22. Morphological features of normal and abnormal viable evaginated cysticerci and some released ones from two mass cysticerci surrounding with a transparent membrane.

19. A 62 day-old evaginated cysticercus with a rostellum, 4 suckers, a big bladder, and a long protoscolex filled with numerous dark brown calcareous corpuscles (Bar = 100 µm).

20. Three abnormal cysticerci each had two protoscleces (Bar = 100 µm).

21. Enlarged Fig. 19. A rostellum, 2 suckers, and several large inner hooks and numerous small outer hooks (Bar = 30 µm).

22. Two mass of cysticerci surrounding each with a transparent membrane and some releasing invaginated and evaginated ones.

Table 1.Viable cysticercus recovery and weight and size of the tumor-like cyst in 10 SCID mice each infected with 39,000 oncospheres of Taenia saginata asiatica

Table 1.

|

Mice No. |

Age of infection (days) |

Cysticercus recovery

|

Weight (gm)

|

Size (in diameter)

|

|

No. |

% |

Mousea)

|

Tumorb)

|

Tumor (cm) |

Cysticercus (mm) |

|

1 |

38 |

178 |

0.5 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

|

2 |

62 |

1,794(3) |

4.6 |

26 |

9.6 |

3.0 |

2(1-3) |

|

3 |

89 |

125 |

0.3 |

23 |

3.5 |

3.0 |

3(2-4) |

|

4 |

118 |

529(3) |

1.4 |

27 |

5.0 |

3.2 |

4(2-5) |

|

5 |

145 |

649(3) |

1.7 |

24 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

3(2-5) |

|

6 |

175 |

323 |

0.8 |

27c)

|

1.5, 2.5 |

1.5, 2.5 |

4(2-5) |

|

7 |

215 |

557 |

1.4 |

23 |

5.0 |

4.3 |

4(2-6) |

|

8 |

244 |

850 |

2.2 |

24 |

4.0 |

3.5 |

5(3-6) |

|

9 |

244 |

660 |

1.7 |

22 |

3.5 |

3.0 |

5(3-6) |

|

10 |

244 |

234 |

0.6 |

22 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

4(3-6) |

|

|

Mean |

157 |

590 |

1.5 |

24 |

4 |

3.2 |

4 |

|

Range |

38-244 |

125-1,794 |

0.3-4.6 |

22-27 |

1.5-9.6 |

1.5-4.3 |

1-6 |

Table 2.Measurement and count of evaginated cysticerci of Taenia saginata asiatica in six SCID mice

Table 2.

|

|

Scolex (μm)

|

Protoscolex (μm)

|

Bladder (μm)

|

Rostellar hook

|

|

Days of infection |

No. exam. |

Length |

Width |

Sucker (μm) (diameter) |

Rostellum (μm) (diameter) |

No. of segments |

Length |

Width |

Length |

Width |

No. of rows |

Inner hooksa)

|

|

No. |

Length (μm) |

|

62 |

100 |

336 |

436 |

199 |

67 |

5 |

307 |

513 |

1,044 |

1,042 |

2 |

11 |

5 |

|

|

210-580 |

280-585 |

115-260 |

48-91 |

1-11 |

50-450 |

50-950 |

635-1,370 |

590-1,550 |

|

6-16 |

3-14 |

|

89 |

40 |

341 |

411 |

166 |

68 |

5 |

464 |

606 |

950 |

874 |

2 |

16 |

8 |

|

|

205-490 |

305-540 |

120-220 |

55-90 |

1-10 |

105-780 |

144-950 |

450-1,430 |

425-1,550 |

|

12-25 |

4-15 |

|

118 |

50 |

369 |

466 |

213 |

69 |

4 |

358 |

609 |

1,494 |

1,592 |

2 |

18 |

6 |

|

|

240-525 |

360-590 |

170-255 |

30-90 |

1-12 |

190-610 |

118-955 |

870-2,235 |

1,055-2,180 |

|

12-20 |

3-12 |

|

145 |

50 |

538 |

591 |

233 |

76 |

8 |

848 |

870 |

1,518 |

1,532 |

2 |

16 |

12 |

|

|

270-1,050 |

425-865 |

165-300 |

45-115 |

2-20 |

150-2,900 |

570-1,360 |

820-2,300 |

525-2,180 |

|

14-18 |

8-18 |

|

175 |

50 |

606 |

694 |

252 |

57 |

5 |

785 |

790 |

1,724 |

1,752 |

2 |

19 |

11 |

|

|

400-915 |

500-920 |

215-295 |

35-75 |

2-9 |

150-1,550 |

510-2,165 |

840-4,240 |

855-3,900 |

|

12-23 |

3-16 |

|

215 |

50 |

789 |

787 |

265 |

83 |

9 |

2,162 |

1,165 |

3,199 |

3,325 |

2 |

16 |

13 |

|

|

525-1,090 |

620-915 |

221-315 |

41-94 |

3-18 |

1,210-2,950 |

890-1,525 |

2,630-4,775 |

2,660-4,240 |

|

13-19 |

5-18 |

|

|

Total |

340 |

477 |

558 |

220 |

70 |

6 |

756 |

727 |

1,586 |

1,615 |

2 |

16 |

9 |

|

(62-215) |

|

205-1,090 |

280-920 |

115-315 |

30-115 |

4-9 |

50-2,950 |

50-2,165 |

450-4,775 |

425-4,240 |

|

6-25 |

3-18 |

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Experimental animal models and their use in understanding cysticercosis: A systematic review

Muloongo C. Sitali, Veronika Schmidt, Racheal Mwenda, Chummy S. Sikasunge, Kabemba E. Mwape, Martin C. Simuunza, Clarissa P. da Costa, Andrea S. Winkler, Isaac K. Phiri, Adler R. Dillman

PLOS ONE.2022; 17(7): e0271232. CrossRef - Taeniasis and cysticercosis in Asia: A review with emphasis on molecular approaches and local lifestyles

Akira Ito, Tiaoying Li, Toni Wandra, Paron Dekumyoy, Tetsuya Yanagida, Munehiro Okamoto, Christine M Budke

Acta Tropica.2019; 198: 105075. CrossRef - Opinion of the Scientific Panel on biological hazards (BIOHAZ) on the suitability and details of freezing methods to allow human consumption of meat infected with Trichinella or Cysticerc

EFSA Journal.2005; 3(1): 142. CrossRef - Development of Taenia saginata asiatica metacestodes in SCID mice and its infectivity in human and alternative definitive hosts

S. L. Chang, N. Nonaka, M. Kamiya, Y. Kanai, H. K. Ooi, W. C. Chung, Y. Oku

Parasitology Research.2005; 96(2): 95. CrossRef