Abstract

Acanthamoeba cysts are resistant to unfavorable physiological conditions and various disinfectants. Acanthamoeba cysts have 2 walls containing various sugar moieties, and in particular, one third of the inner wall is composed of cellulose. In this study, it has been shown that down-regulation of cellulose synthase by small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly inhibits the formation of mature Acanthamoeba castellanii cysts. Calcofluor white staining and transmission electron microscopy revealed that siRNA transfected amoeba failed to form an inner wall during encystation and thus are likely to be more vulnerable. In addition, the expression of xylose isomerase, which is involved in cyst wall formation, was not altered in cellulose synthase down-regulated amoeba, indicating that cellulose synthase is a crucial factor for inner wall formation by Acanthamoeba during encystation.

-

Key words: Acanthamoeba castellanii, encystation, cellulose synthase, endocyst

INTRODUCTION

Pathogenic

Acanthamoeba is a causative agent of granulomatous amoebic encephalitis and amoebic keratitis [

1]. The life cycle of

Acanthamoeba consists of 2 stages, trophozoite and cyst, and the latter is resistant to extreme physical and chemical conditions [

1]. To understand the encystation mechanism and improve the treatment of amoebic infections, encystation-mediating factors have been studied. The up-regulation of 701 genes has been reported during the encystation of

Acanthamoeba [

2], and actin dynamics [

3], autophagosome structure related proteins [

4,

5], cyst specific serine and cysteine proteases were identified [

6,

7,

8,

9]. In this study, we focused on the cyst wall related genes of

Acanthamoeba.

The mature cyst wall of

Acanthamoeba consists of an outer layer (the ectocyst) and an inner layer (the endocyst) separated by a space [

10]. The ectocyst is composed of a combination of proteins and polysaccharides [

11], whereas the endocyst is composed primarily of cellulose [

12]. Therefore, cellulose synthesis is a potential therapeutic target [

13]. The cellulose in

Acanthamoeba cyst walls can also be used for a diagnosis based on CBD (the cellulose-binding domain of

Clostridium cellulovorans) [

14].

Cellulose biosynthesis in

Acanthamoeba is achieved by converting cellular glycogen into glucose via glycogen phosphorylase [

15,

16]. For this purpose, glycogen phosphorylase, UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, and cellulose synthase are expressed at high levels during encystation [

16]. Aqeel et al. [

17] reported that siRNA silencing of xylose isomerase or cellulose synthase inhibits the encystation of

Acanthamoeba, as determined by counting mature cysts resistant to SDS.

Here, we describe structural changes in the cyst wall of Acanthamoeba castellanii Castellani and the inhibition of encystation by transfection with siRNA against cellulose synthase (GenBank no. JX312799). In addition, we examined the effects of down-regulation of cellulose synthase on the expression patterns of xylose isomerase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Amoeba cultivation and encystation

A. castellanii (ATCC 30011) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection.

Acanthamoeba trophozoites were cultured axenically in PYG medium, which contains proteose peptone 0.75% (w/v), yeast extract 0.75% (w/v), and glucose 1.5% (w/v) at 25℃ in a Sanyo incubator (San Diego, California, USA).

Acanthamoeba cysts were induced in encystation media (0.1 M KCl, 0.008 M MgSO

4, 0.0004 M CaCl

2, and 0.02 M 2-amino-2-methyl-1,3-propanediol, pH 9.0) for 3 days [

10]. Mature cysts were counted under a light microscope after treatment with 0.5% SDS to calculate encystation ratios [

17].

Gene expression analysis based on real-time PCR

Total RNA was purified using TRIzol Reagent (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Maryland, USA), and cDNA synthesis was conducted using a RevertAidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Hanover, Indiana, USA). Real-time PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM® 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA), using the default thermocycler program for all genes [

9] and sense and anti-sense primers (sense 5'-TCATCTACATGTTCTGCGCCC and antisense 5'-CGATCCAGTTGTTGAGCATGC for cellulose synthase, and sense 5'-AGTACGAGATGCTCCTCAACCG and antisense 5'-TCTCGACAA GACGAAGAGGTCC for xylose isomerase). The cDNA sequence information of xylose isomerase was obtained from differentially expressed gene analysis [

7]. All reaction mixtures were made using Sybr Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Otsu, Shiga, Japan). The 18S ribosomal DNA was used as the reference gene [

9]. Real-time PCR was performed to determine relative gene expressions using the 2-ΔΔCT method, and experiments were performed in triplicate.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting cellulose synthase of

A. castellaniii was synthesized by Sigma-Proligo (Boulder, Colorado, USA), based on its cDNA sequence. The siRNA duplex with sense (5'-GAUCGAGUACUUCAACAUCdTdT) and anti-sense (5'-GAUGUUGAAGUACUCGAUCdTdT) against cellulose synthase were used. The siRNA (4 µg) was transfected into

A. castellanii trophozoites at a cell density of 4×10

5 per well as previously described [

4]. As a negative control, siRNA with a scrambled sequence (Ambion, Austin, Texas, USA) absent in

Acanthamoeba was used.

Acanthamoeba were incubated in encystation media for 3 days with or without siRNA against cellulose synthase. After the induction of encystation, amoeba pellets were resuspended in 2.5% calcofluor white staining solution and incubated for 20 min at room temperature [

13]. After washing with PBS, samples were observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy

Acanthamoeba were prefixed with 4% glutaraldehyde and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. Fixed cells were dehydrated with ethyl alcohol, treated with propylene oxide-resin, and embedded in resin. Ultrathin sections were cut and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate [

9]. Samples were observed under a Hitachi H-7000 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean±SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed by an unpaired Student's t-test. A P-value of <0.01 was interpreted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

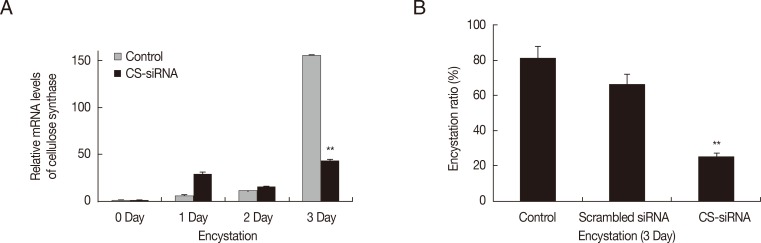

Gene silencing of cellulose synthase by siRNA

Gene silencing by siRNA was used to determine the involvement of cellulose synthase (CS) in encystation of

Acanthamoeba. The mRNA level of cellulose synthase was highly expressed at day 3 after induction of encystation (

Fig. 1A-

). After transfection of CS-siRNA, a significant decrease in the mRNA expression of cellulose synthase was observed at day 3 after induction of encystation (

Fig. 1A-

), showing that the encystation of

Acanthamoeba was significantly inhibited by silencing of cellulose synthase (

Fig. 1B). Scrambled negative siRNA had no effects on

Acanthamoeba encystation.

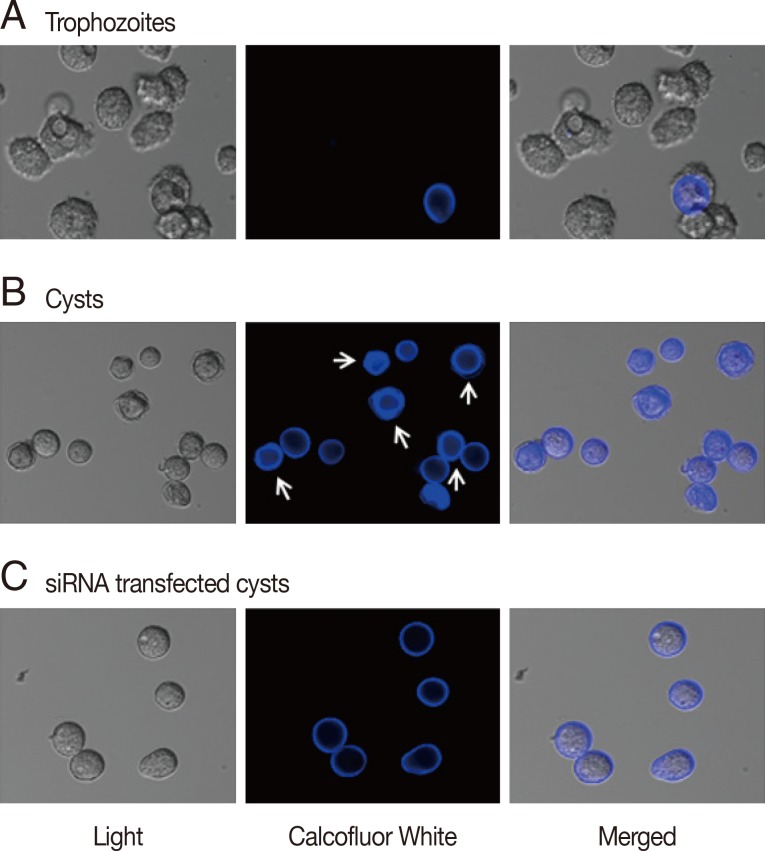

To determine the effects of gene silencing of cellulose synthase (CS) on encystation of

Acanthamoeba, calcofluor white staining and transmission electron microscopy were performed. As shown in

Fig. 2A, calcofluor staining was not observed in trophozoites. Interestingly, at day 3 post-induction, 2 different patterns of calcofluor positive materials were observed on cyst surfaces (

Fig. 2B). Young cysts had a single layer of calcofluor stained, whereas mature cysts exhibited a double layer of calcofluor stained cells. An endocyst, containing a larger amount of cellulose than an ectocyst, showed a strong staining reaction (

Fig. 2B, arrows). In CS-siRNA transfected amoeba, single layered young cysts predominated at day 3 post-induction, whereas in non-transfected amoeba, double layered mature cysts were observed (

Fig. 2C).

To confirm the inhibition of cyst maturation by CS-siRNA, normal mature cysts and CS-siRNA transfected cysts were observed under a transmission electron microscope (TEM). After normal induction of encystation,

Acanthamoeba formed mature cysts with double cyst walls (

Fig. 3A). Ectocysts were deeply wrinkled and electron-dense, whereas smooth-organized endocysts were closely associated with the inner cellular membrane. In contrast, CS-siRNA transfected

Acanthamoeba showed significant impairment of cyst morphology. Cells were shrunken and lost contact with cyst walls, which lost their compactness, and ectocysts were lightly stained with few or no wrinkles. Furthermore, endocysts were not observed. The majority of CS-siRNA transfected

Acanthamoeba remained as single walled young cysts or died (

Fig. 3B).

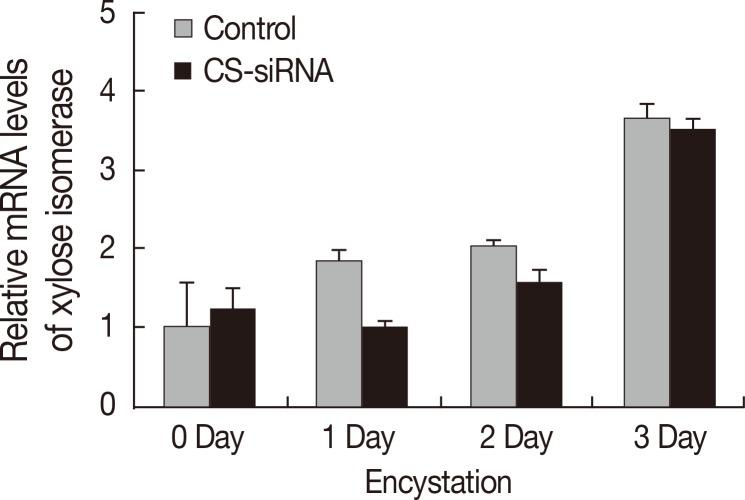

Real-time PCR was conducted to examine the effects of CS-siRNA on expression of xylose isomerase in

Acanthamoeba. Silencing of cellulose synthase during the encystation of

Acanthamoeba had no effects on expression of xylose isomerase (

Fig. 4). In fact, the expression pattern of xylose isomerase in CS-siRNA transfected amoeba was similar to that in normal untransfected controls.

DISCUSSION

During encystation,

Acanthamoeba transforms to a double-walled mature cyst via a single-walled young cyst (immature cyst or precyst) [

15], and fully matured cysts resist physical, chemical, and radiological insults [

18]. For example, mature cysts are resistant to 0.5% SDS and able to excyst on agar plates, whereas single-walled precysts cannot survive this exposure and undergo lysis [

15]. The resistance of mature cysts is probably due to the formation of a dense, almost impermeable wall structure [

10,

19].

The key component of the

Acanthamoeba inner cyst wall is cellulose [

20,

21], and a efficient, rapid process for cyst wall construction involving glycogen degradation and cellulose synthesis has been hypothesized [

16]. During the encystation of

Acanthamoeba, glycogen phosphorylase and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase are expressed at high levels [

16]. In

A. castellanii Neff, glycogen phosphorylase knockdown caused a dramatic decrease in the number of mature cysts and increase in the number of immature cysts [

15]. Furthermore, the inhibition of cellulose synthase using siRNA reduced encystation by more than 50% in

A. castellanii Neff [

17], and the cellulose synthesis inhibitor DCB (2,6-dichlorobenzonitrile) blocked the encystation of

Acanthamoeba keratitis isolate [

13]. These results suggest that targeting of cellulose synthesis could be used as a strategy for treatment of

Acanthamoeba infection. In addition, an understanding of the role of cellulose in association with cyst wall formation would undoubtedly aid the development of novel treatments.

Our results confirmed the notion that cellulose is the main component of the inner cyst wall of Acanthamoeba, and showed that silencing of cellulose synthase inhibits cyst maturation. In our study, the silencing of cellulose synthase by siRNA in A. castellanii revealed that inner wall formation was inhibited based on the counting of mature cysts after treatment with SDS, calcofluor white staining, and electron microscopy. Furthermore, the inhibition of cellulose synthase caused young cysts to be produced and blocked progression to the mature double-walled state.

Aqeel et al. [

17] proposed that xylose biosynthesis could replace cellulose biosynthesis and result in hemicellulose incorporation into the cyst wall and immature cyst formation. To confirm the relation between cellulose biosynthesis and xylose production in encystation, we analyzed the expression patterns of xylose isomerase in cellulose synthase down-regulated cells. We found that the expression level of xylose isomerase in CS-siRNA transfected amoeba was almost the same as that in normal controls (

Fig. 4). Cellulose synthase and xylose isomerase are expressed independently in encysting

Acanthamoeba, and in the present study, the expression patterns of cellulose synthase and xylose isomerase confirmed that both importantly contribute to the cyst wall formation during encystation of

Acanthamoeba, and that one cannot replace the other.

Our observations provided an important information for those seeking to develop appropriate anti-amoebic drugs or sterilizing solutions against Acanthamoeba. In addition, we believe that our results could be applied to vascular plants, algae, and bacteria in which cellulose is a major cell wall component.

Basic Science Research Program of the Korean National Research FoundationNRF-2013R1A1A3012066

Notes

-

We declare that we have no conflict of interest related to this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the Korean National Research Foundation (NRF-2013R1A1A3012066).

References

- 1. Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. Acanthamoeba spp. as agents of disease in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003;16:273-307.

- 2. Moon EK, Xuan YH, Chung DI, Hong Y, Kong HH. Microarray analysis of differentially expressed genes between cysts and trophozoites of Acanthamoeba castellanii. Korean J Parasitol 2011;49:341-347.

- 3. Bouyer S, Rodier MH, Guillot A, Héchard Y. Acanthamoeba castellanii: proteins involved in actin dynamics, glycolysis, and proteolysis are regulated during encystation. Exp Parasitol 2009;123:90-94.

- 4. Moon EK, Chung DI, Hong YC, Kong HH. Autophagy protein 8 mediating autophagosome in encysting Acanthamoeba. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2009;168:43-48.

- 5. Song SM, Han BI, Moon EK, Lee YR, Yu HS, Jha BK, Danne DB, Kong HH, Chung DI, Hong Y. Autophagy protein 16-mediated autophagy is required for the encystation of Acanthamoeba castellanii. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2012;183:158-165.

- 6. Leitsch D, Köhsler M, Marchetti-Deschmann M, Deutsch A, Allmaier G, Duchêne M, Walochnik J. Major role for cysteine proteases during the early phase of Acanthamoeba castellanii encystment. Eukaryot Cell 2010;9:611-618.

- 7. Moon EK, Chung DI, Hong YC, Kong HH. Differentially expressed genes of Acanthamoeba castellanii during encystation. Korean J Parasitol 2007;45:283-285.

- 8. Moon EK, Chung DI, Hong YC, Kong HH. Characterization of a serine proteinase mediating encystation of Acanthamoeba. Eukaryot Cell 2008;7:1513-1517.

- 9. Moon EK, Hong Y, Chung DI, Kong HH. Cysteine protease involving in autophagosomal degradation of mitochondria during encystation of Acanthamoeba. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2012;185:121-126.

- 10. Bowers B, Korn ED. The fine structure of Acanthamoeba castellanii (Neff strain). II. Encystment. J Cell Biol 1969;41:786-805.

- 11. Neff RJ, Neff RH. The biochemistry of amoebic encystment. Symp Soc Exp Biol 1969;23:51-81.

- 12. Linder M, Winiecka-Krusnell J, Linder E. Use of recombinant cellulose-binding domains of Trichoderma reesei cellulase as a selective immunocytochemical marker for cellulose in protozoa. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002;68:2503-2508.

- 13. Dudley R, Alsam S, Khan NA. Cellulose biosynthesis pathway is a potential target in the improved treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007;75:133-140.

- 14. Derda M, Hadas E. Use of the presence of cellulose in cellular wall of Acanthamoeba cysts for diagnostic purposes. Wiad Parazytol 2009;55:47-51.

- 15. Lorenzo-Morales J, Kliescikova J, Martinez-Carretero E, De Pablos LM, Profotova B, Nohynkova E, Osuna A, Valladares B. Glycogen phosphorylase in Acanthamoeba spp.: determining the role of the enzyme during the encystment process using RNA interference. Eukaryot Cell 2008;7:509-517.

- 16. Moon EK, Kong HH. Short-cut pathway to synthesize cellulose of encysting Acanthamoeba. Korean J Parasitol 2012;50:361-364.

- 17. Aqeel Y, Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Silencing of xylose isomerase and cellulose synthase by siRNA inhibits encystation in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Parasitol Res 2013;112:1221-1227.

- 18. Aksozek A, McClellan K, Howard K, Niederkorn JY, Alizadeh H. Resistance of Acanthamoeba castellanii cysts to physical, chemical, and radiological conditions. J Parasitol 2002;88:621-623.

- 19. Khunkitti W, Hann AC, Lloyd D, Furr JR, Russell AD. Biguanide-induced changes in Acanthamoeba castellanii: an electron microscopic study. J Appl Microbiol 1998;84:53-62.

- 20. Dudley R, Jarroll EL, Khan NA. Carbohydrate analysis of Acanthamoeba castellanii. Exp Parasitol 2009;122:338-343.

- 21. Tomlinson G, Jones EA. Isolation of cellulose from the cyst wall of a soil amoeba. Biochim et Biophys Acta 1962;63:194-200.

Fig. 1Transfection of

Acanthamoeba with siRNA against cellulose synthase. Cellulose synthase (CS) was highly expressed during encystation (A-

), but was down-regulated in CS-siRNA transfected cells (A-

). This inhibition by CS-siRNA was found to reduce encystation ratios (>50% inhibition of mature cyst formation) (B). The experiments were repeated 3 times and the average values are presented with error bars representing standard deviations.

**Means were significantly different by the Student's

t-test (

P<0.01).

Fig. 2Cyst wall formation as detected by calcofluor white staining. (A) Cellulose was not present in trophozoites by calcofluor white staining. (B) At day 3 after the induction of encystation, young cysts and mature cysts (arrows) were observed. (C) The majority of cellulose synthase siRNA transfected cells were young or immature cysts.

Fig. 3Cyst wall formation as detected by scanning electron microscopy. (A) Acanthamoeba trophozoites were transformed into mature cysts with 2 cyst walls (the ectocyst and endocyst). (B) In contrast to normal cells, cellulose synthase siRNA transfected cells did not form 2 cyst walls and remained as young cysts or died.

Fig. 4The expression pattern of xylose isomerase. Xylose isomerase was expressed high in

Acanthamoeba during encystation (

). After transfection with cellulose synthase siRNA, the expression pattern of xylose isomerase was unchanged (

). Accordingly, the down-regulation of cellulose synthase had no effects on the expression of xylose isomerase in

Acanthamoeba.

). After transfection of CS-siRNA, a significant decrease in the mRNA expression of cellulose synthase was observed at day 3 after induction of encystation (Fig. 1A-

). After transfection of CS-siRNA, a significant decrease in the mRNA expression of cellulose synthase was observed at day 3 after induction of encystation (Fig. 1A- ), showing that the encystation of Acanthamoeba was significantly inhibited by silencing of cellulose synthase (Fig. 1B). Scrambled negative siRNA had no effects on Acanthamoeba encystation.

), showing that the encystation of Acanthamoeba was significantly inhibited by silencing of cellulose synthase (Fig. 1B). Scrambled negative siRNA had no effects on Acanthamoeba encystation. ), but was down-regulated in CS-siRNA transfected cells (A-

), but was down-regulated in CS-siRNA transfected cells (A- ). This inhibition by CS-siRNA was found to reduce encystation ratios (>50% inhibition of mature cyst formation) (B). The experiments were repeated 3 times and the average values are presented with error bars representing standard deviations. **Means were significantly different by the Student's t-test (P<0.01).

). This inhibition by CS-siRNA was found to reduce encystation ratios (>50% inhibition of mature cyst formation) (B). The experiments were repeated 3 times and the average values are presented with error bars representing standard deviations. **Means were significantly different by the Student's t-test (P<0.01).

). After transfection with cellulose synthase siRNA, the expression pattern of xylose isomerase was unchanged (

). After transfection with cellulose synthase siRNA, the expression pattern of xylose isomerase was unchanged ( ). Accordingly, the down-regulation of cellulose synthase had no effects on the expression of xylose isomerase in Acanthamoeba.

). Accordingly, the down-regulation of cellulose synthase had no effects on the expression of xylose isomerase in Acanthamoeba.