Abstract

Members of genus Acanthamoeba are widely distributed in the environment. Some are pathogenic and cause keratitis and fatal granulomatous amoebic encephalitis. In this study, we isolated an Acanthamoeba CJW/W1 strain from tap water in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China. Its 18S rDNA was sequenced and a phylogenetic tree was constructed. The isolated cysts belonged to morphologic group II. Comparison of 18S rDNA sequences of CJW/W1 strain and other isolates showed high similarity (99.7%) to a clinical isolate Asp, KA/E28. A phylogeny analysis confirmed this isolate belonged to the pathogenic genotype T4, the most common strain associated with Acanthamoeba-related diseases. This is the first report of an Acanthamoeba strain isolated from tap water in Wuxi, China. Acanthamoeba could be a public health threat to the contact lens wearers and, therefore, its prevalence should be monitored.

-

Key words: Acanthamoeba, tap water, Wuxi

Free-living amoebas (FLAs), including

Acanthamoeba, are widely distributed in the environment, including soil, air, and water [

1]. There are 2 stages in the life cycle of

Acanthamoeba. The active stage is a trophozoite. Under adverse conditions, the amoeba forms a double-walled cyst. This double wall barrier allows cysts to resist chemical and physical disinfectant treatments, leading to difficulties in controlling related diseases [

2].

Some strains of

Acanthamoeba are opportunistic pathogens, causing granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE) and

Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK). Furthermore, the diagnosis of AK can pose a challenge. The disease can be misdiagnosed as bacterial or fungal keratitis, thus delaying therapy and potentially leading to aggravation of the disease [

3]. The number of infection cases is increasing every year owing to the increase in the number of contact lens wearers who do not comply with recommended hygiene practices and even rinse their contact lenses with tap water [

4,

5]. Additionally, an increase in the number of cases of AK has been reported in China [

6]. Because of all the threats and their dangerous effects on human health, the early detection of pathogenic

Acanthamoeba in environments is essential.

Currently, 20 genotypes of

Acanthamoeba—T1 to T20—have been identified. Earlier studies have shown that T3, T4, and T5 genotypes are highly pathogenic [

7]. Furthermore, the T4 genotype is the most reported in the literature from AK clinical cases and is also the most prevalent in the environment [

8]. However, a clear relationship between the genotypes and their pathogenicity has not been established. Molecular techniques based on the amplification of nucleic acids are optimal for sensitive, specific, and simultaneous detection and quantification of protozoa compared with conventional staining and microscopy assays [

9]. Moreover, sequencing data of the nuclear small subunit ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) and genotyping systems provide distinct strain phylogeny and taxonomy [

2].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the occurrence, genotypic characterization, and potential pathogenicity of Acanthamoeba spp. in tap water from selected locations in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China, using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Sixty tap water samples were collected from public places randomly distributed in 5 subareas in Wuxi. We isolated an

Acanthamoeba CJW/W1 strain from tap water, which we cultured axenically in PYG medium [

10]. An EasyPure® Genomic DNA Kit (Transgenbiotech, Beijing, China) was used to extract genomic DNA and 18S rDNA from

Acanthamoeba was amplified [

10]. The sequencing data were aligned with the strains of

Acanthamoeba and 18S rDNA sequences with a high degree of similarity in the GenBank database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search engine. The phylogenic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with MEGA 7.

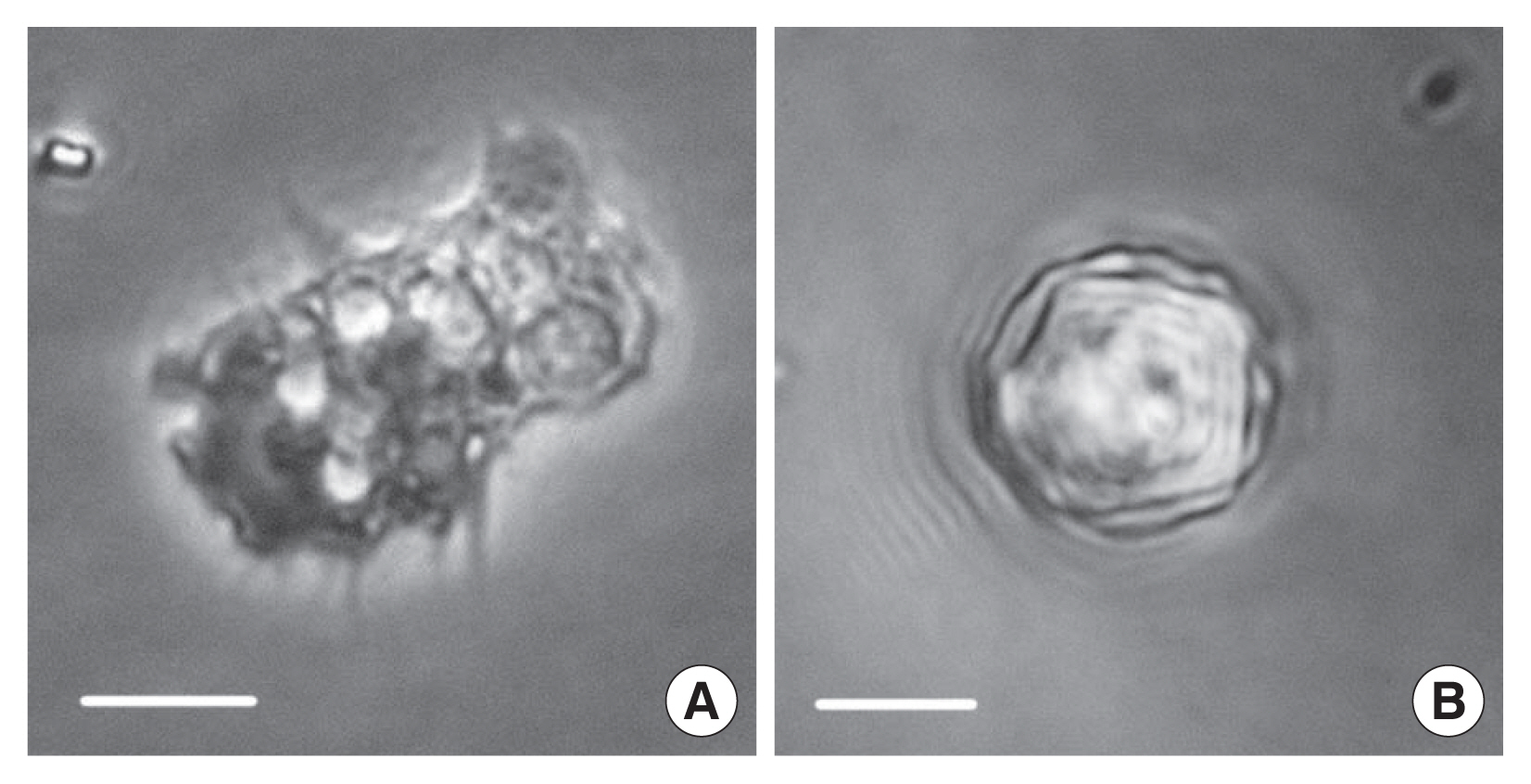

Fig. 1 shows a trophozoite and cyst of the isolate CJW/W1 from tap water of Wuxi. The trophozoite of the isolated amoebae had a large single nucleus and spine-like pseudopodia, characteristic features of the genus

Acanthamoeba. The cyst had polygonal and corrugated ectocysts. We randomly selected 50 cysts from the culture bottle. The number of arms of the cysts ranged from 3 to 7 and the diameter ranged from 13.0 to 23.1 μm. Studies have reported that

Acanthamoeba can be classified into 3 main groups based on morphological differences of the cysts [

11,

12]. Group I has a radial endocyst with a well-separated ectocyst, group II has a polygonal endocyst with a usually corrugated ectocyst, and group III has a round endocyst without cyst arms and a usually smooth ectocyst. The morphologic characteristics of the cysts of isolate CJW/W1 revealed that they belonged to group II. The majority of reported human diseases caused by

Acanthamoeba (AK and GAE) and strains isolated from the environment are associated with group II [

11], which is similar to the results of other studies [

10].

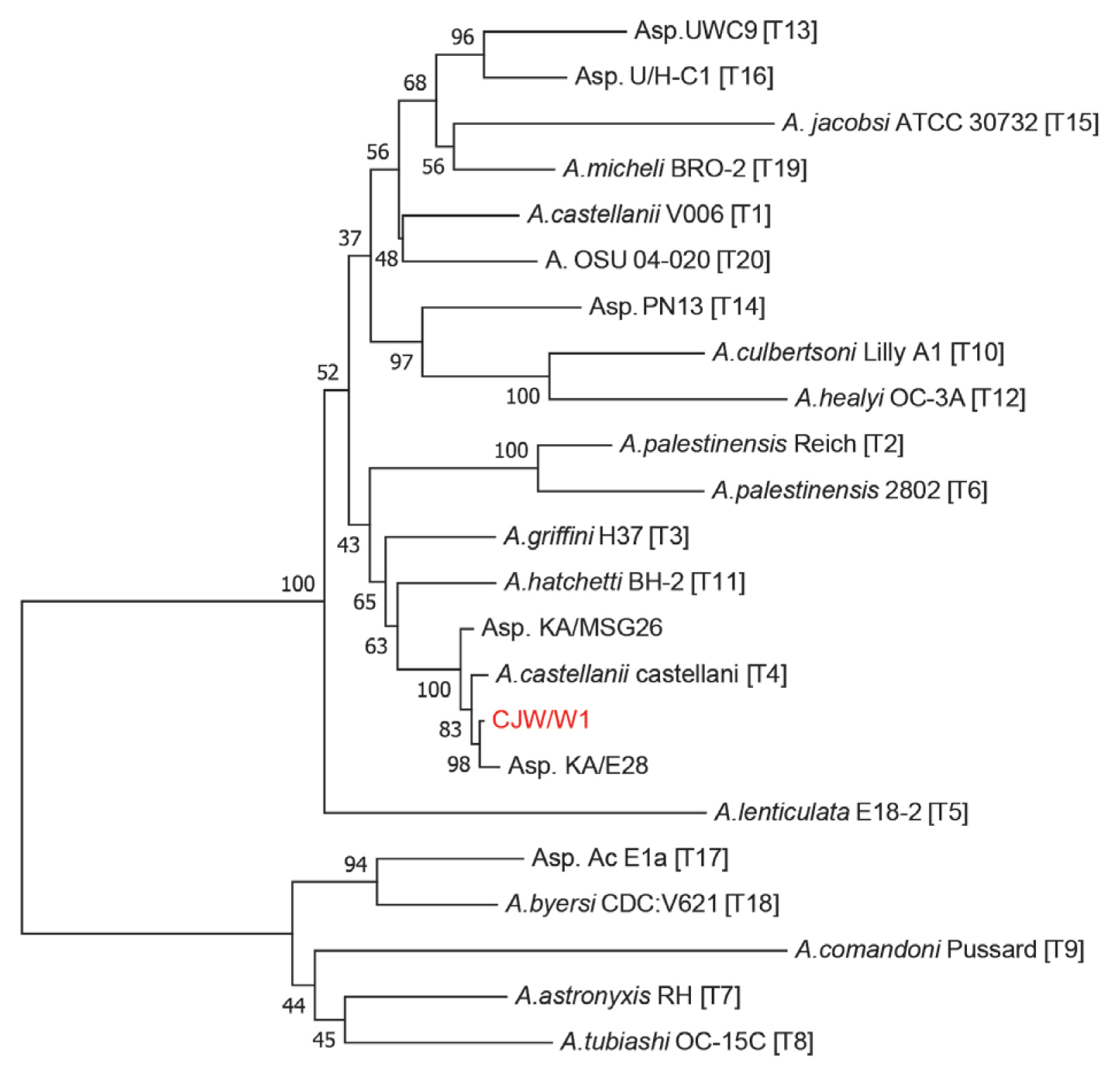

According to the sequencing results, the length of the nuclear 18S rDNA fragment of

Acanthamoeba CJW/W1 is 2,315 bp, which is close to the range of 2,300–2,700 bp reported by Stothard et al. [

13]. Besides

Acanthamoeba CJW/W1, representatives of all genotypes of

Acanthamoeba (T1–T20) and their close relatives were selected for phylogenetic analysis. The BLAST result demonstrated that the 18S rDNA sequence shared 99.7% similarity with both Asp. KA/MSG26 and Asp. KA/E28, which were isolated from marine sediments in Sunchen, Gangjin, Korea and infected cornea of amoebic keratitis patients in Korea, respectively. As shown in

Fig. 2, we confirmed

Acanthamoeba CJW/W1 had high homology with

Acanthamoeba genotype T4 and Asp. KA/E28. Additionally, genotype T4 presented high pathogenicity associated with both AK and more invasive diseases [

9]. In conclusion,

Acanthamoeba CJW/W1 could be a potential public health threat. To demonstrate our inference, reliable in vivo pathogenicity tests on mice should be conducted. In other studies,

Acanthamoeba spp. have been detected in tap water in Mexico, Iran, and Spain with 22.5%, 48%, and even 100% positive samples, respectively [

14]. The positive rate of

Acanthamoeba in this study was relatively low, suggesting a very low prevalence of

Acanthamoeba in tap water. This is in agreement with the available clinical AK case records from this area. Furthermore, there could be some mutation-induced changes in gene structure during the repeated passage of

Acanthamoeba [

15]. Previous studies have often used 3 methods to evaluate the prevalence of

Acanthamoeba in environmental material: conventional PCR, real-time PCR, and LAMP, all based on 18S rRNA genes. Considering its high sensitivity, the LAMP method is highly recommended, followed by real-time PCR techniques [

1,

5]. Nevertheless, in order to isolate and preserve

Acanthamoeba strains, and to obtain complete 18S rDNA fragments, we chose the conventional PCR method. As we expect a higher presence of

Acanthamoeba, more and larger samples should be tested to estimate the prevalence of this organism in water using other methods mentioned above.

Some strains of

Acanthamoeba spp. can cause serious human diseases, such as fatal GAE and AK, a vision-threatening corneal infection [

16]. Moreover,

Acanthamoeba acts as a transmission vehicle for bacteria and fungi [

17]. The discovery of a high rate of specific antibodies (up to 100%) in healthy populations confirmed that humans are frequently exposed to

Acanthamoeba [

18]. Thus, not only users of contact lenses, but also humans with reduced or impaired immune status due to AIDS, immunosuppressive therapy, malnutrition, diabetes, pregnancy, and alcoholism are prone to infection.

We detected

Acanthamoeba spp. in treated water from drinking water treatment plants, indicating that the purification processes used in these treatment plants did not eliminate these protozoans. Furthermore,

Acanthamoeba can be resistant to chlorination, a purification process, which is in accordance with the findings in other countries [

14]. A higher prevalence of FLA has been observed in tap water than in the natural water source, because microorganisms that settle on the inner wall of water pipes become a source of food for

Acanthamoeba [

19]. Therefore, rinsing contact lenses with tap water or home-made saline solutions and showering or swimming wearing lenses are high risk factors for eye infections. Consequently, it is important to develop programs to promote awareness toward the existence of potential pathogenic

Acanthamoeba, the risk of infection for immunocompromised populations, and better hygienic practices among contact lens wearers [

8]. Furthermore, these results should be made available for all medical practitioners to manage their patients and susceptible populations with adequate care and to organize proper control programs.

Notes

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to appreciate very much for the financial support by Public Health Research Center at Jiangnan University (No. JUPH201501), Wuxi Science and Technology Development Fund (No. CSE31N1627), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. JUSRP11571) and University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program in Jiangsu Province (201710295040X).

Fig. 1Morphology of trophozoite (A) and cyst (B) of Acanthamoeba CJW/W1. Bar=10 μm.

Fig. 2Molecular phylogeny of the genus Acanthamoeba, based on full 18S rDNA sequence. Genotypes were indicated with their main species types. A phylogenetic tree showed correlation between CJW/W1 and Acanthamoeba spp. The bootstrap values (BV) (100 replicates) were shown at the nodes on the Neighbor-joining tree.

References

- 1. Lass A, Guerrero M, Li X, Karanis G, Ma L, Karanis P. Detection of Acanthamoeba spp. in water samples collected from natural water reservoirs, sewages, and pharmaceutical factory drains using LAMP and PCR in China. Sci Total Environ 2017;584–585:489-494.

- 2. Corsaro D, Köhsler M, Montalbano Di Filippo M, Venditti D, Monno R, Di Cave D, Berrilli F, Walochnik J. Update on Acanthamoeba jacobsi genotype T15, including full-length 18S rDNA molecular phylogeny. Parasitol Res 2017;116:1273-1284.

- 3. Wang Y, Feng X, Jiang L. Current advances in diagnostic methods of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Chin Med J 2014;127:3165-3170.

- 4. Risler A, Coupat-Goutaland B, Pélandakis M. Genotyping and phylogenetic analysis of Acanthamoeba isolates associated with keratitis. Parasitol Res 2013;112:3807-3816.

- 5. Gomes Tdos S, Magnet A, Izquierdo F, Vaccaro L, Redondo F, Bueno S, Sánchez ML, Angulo S, Fenoy S, Hurtado C, Del Aguila C. Acanthamoeba spp. in Contact Lenses from Healthy Individuals from Madrid, Spain. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154246.

- 6. Zhong J, Li X, Deng Y, Chen L, Zhou S, Huang W, Lin S, Yuan J. Associated factors, diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis in a referral Center in Southern China. BMC Ophthalmol 2017;17:175.

- 7. Walochnik J, Obwaller A, Aspöck H. Correlations between morphological, molecular biological, and physiological characteristics in clinical and nonclinical isolates of Acanthamoeba spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000;66:4408-4413.

- 8. Shokri A, Sarvi S, Daryani A, Sharif M. Isolation and Genotyping of Acanthamoeba spp. as Neglected Parasites in North of Iran. Korean J Parasitol 2016;54:447-453.

- 9. Moreno Y, Moreno-Mesonero L, Amorós I, Pérez R, Morillo JA, Alonso JL. Multiple identification of most important waterborne protozoa in surface water used for irrigation purposes by 18S rRNA amplicon-based metagenomics. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2018;221:102-111.

- 10. Xuan Y, Shen Y, Ge Y, Yan G, Zheng S. Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba strains from soil and tap water in Yanji, China. Environ Health Prev Med 2017;22:58.

- 11. Qvarnstrom Y, Nerad TA, Visvesvara GS. Characterization of a new pathogenic Acanthamoeba species, A. byersi n. sp., isolated from a human with fatal amoebic encephalitis. J Eukaryot Microbiol 2013;60:626-633.

- 12. Pussard M, Pons R. Morphologie de la paroi kystique et taxonomie du genre Acanthamoeba (Protozoa, Amoebida). Protistologica 1977;13:557-598. (in French).

- 13. Stothard DR, Schroeder-Diedrich JM, Awwad MH, Gast RJ, Ledee DR, Rodriguez-Zaragoza S, Dean CL, Fuerst PA, Byers TJ. The evolutionary history of the genus Acanthamoeba and the identification of eight new 18S rRNA gene sequence types. J Eukaryot Microbiol 1998;45:45-54.

- 14. Magnet A, Galván AL, Fenoy S, Izquierdo F, Rueda C, Fernandez Vadillo C, Pérez-Irezábal J, Bandyopadhyay K, Visvesvara GS, da Silva AJ, del Aguila C. Molecular characterization of Acanthamoeba isolated in water treatment plants and comparison with clinical isolates. Parasitol Res 2012;111:383-392.

- 15. Tawfeek GM, Bishara SA, Sarhan RM, ElShabrawi Taher E, ElSaady Khayyal A. Genotypic, physiological, and biochemical characterization of potentially pathogenic Acanthamoeba isolated from the environment in Cairo, Egypt. Parasitol Res 2016;115:1871-1881.

- 16. Booton GC, Kelly DJ, Chu YW, Seal DV, Houang E, Lam DS, Byers TJ, Fuerst PA. 18S ribosomal DNA typing and tracking of Acanthamoeba species isolates from corneal scrape specimens, contact lenses, lens cases, and home water supplies of Acanthamoeba keratitis patients in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:1621-1625.

- 17. Paterson GN, Rittig M, Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Is Acanthamoeba pathogenicity associated with intracellular bacteria? Exp Parasitol 2011;129:207-210.

- 18. Chappell CL, Wright JA, Coletta M, Newsome AL. Standardized method of measuring acanthamoeba antibodies in sera from healthy human subjects. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001;8:724-730.

- 19. Rożej A, Cydzik-Kwiatkowska A, Kowalska B, Kowalski D. Structure and microbial diversity of biofilms on different pipe materials of a model drinking water distribution systems. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2015;31:37-47.