Abstract

Giardia intestinalis infections arise primarily from contaminated food or water. Zoonotic transmission is possible, and at least 7 major assemblages including 2 assemblages recovered from humans have been identified. The determination of the genotype of G. intestinalis is useful not only for assessing the correlation of clinical symptoms and genotypes, but also for finding the infection route and its causative agent in epidemiological studies. In this study, methods to identify the genotypes more specifically than the known 2 genotypes recovered from humans have been developed using the intergenic spacer (IGS) region of rDNA. The IGS region contains varying sequences and is thus suitable for comparing isolates once they are classified as the same strain. Genomic DNA was extracted from cysts isolated from the feces of 5 Chinese, 2 Laotians and 2 Koreans infected with G. intestinalis and the trophozoites of WB, K1, and GS strains cultured in the laboratory, respectively. The rDNA containing the IGS region was amplified by PCR and cloned. The nucleotide sequence of the 3' end of IGS region was determined and examined by multiple alignment and phylogenetic analysis. Based on the nucleotide sequence of the IGS region, 13 G. intestinalis isolates were classified to assemblages A and B, and assemblage A was subdivided into A1 and A2. Then, the primers specific to each assemblage were designed, and PCR was performed using those primers. It detected as little as 10 pg of DNA, and the PCR amplified products with the specific length to each assemblage (A1, 176 bp; A2, 261 bp; B, 319 bp) were found. The PCR specific to 3 assemblages of G. intestinalis did not react with other bacteria or protozoans, and it did not react with G. intestinalis isolates obtained from dogs and rats. It was thus confirmed that by applying this PCR method amplifying the IGS region, the detection of G. intestinalis and its genotyping can be determined simultaneously.

-

Key words: Giardia intestinalis, intergenic spacer, PCR, genotyping

INTRODUCTION

Giardia intestinalis, a protozoan parasite, is the most frequently detected of the pathogenic intestinal parasites in humans worldwide.

G. intestinalis infections can occur from the consumption of contaminated food and water or though direct contact; after infection the parasite proliferates in the small intestine (

Craun, 1984;

Osterholm et al., 1981). Of all the water-borne diarrhea outbreaks that occurred in the USA from 1971 to 1985, 18% of the cases were reported to be caused by

G. intestinalis (

Craun, 1990).

Since the feces of animals are another source of infection in addition to contaminated food and water, the infection status of

Giardia spp. in animals is also important (

Kirkpatrick and Farrell, 1984). Among the 6 species identified in the

Giardia genus, only

G. intestinalis infects humans.

G. intestinalis infects other animals including cats, dogs, rats, hoofed livestock, and wild mammals as well (

Adam, 2001;

Lalle et al., 2005;

Thompson et al., 2000). Isolates of

G. intestinalis are classified into 7 assemblages (A-G), based on the characterization of the glutamate dehydrogenase (

gdh), elongation factor 1α, small-subunit (SSU) rRNA, and triose phosphate isomerase (

tpi) genes etc (

Hopkins et al., 1997;

Monis et al., 1999;

Read et al., 2004;

Sulaiman et al., 2003). Of 7 assemblages only assemblages A and B were identified among human isolates. These 2 assemblages have also been identified in other host isolates. To effectively prevent infection, an understanding of the infection route and the source of

G. intestinalis that may be zoonotic is important. A study on the cross-infectivity between different host species is also a prerequisite.

Antigen detection immunoassays are developed for routine diagnosis for

Giardia infection (

Garcia and Shimizu, 1997;

Johnston et al., 2003). However, the methods are unable to identify the genotype of

G. intestinalis. Among the diagnostic tools for the detection of

G. intestinalis, the method that detects genetic material has been emphasized recently over others for its higher specificity and sensitivity. The methods using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been applied, which amplifies 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (

Baruch et al., 1996;

Hopkins et al., 1997;

Weiss et al., 1992), ITS regions and 5.8S rDNA (

Hunt et al., 2000), triose phosphate isomerase (

tpi) (

Sulaiman et al., 2003), glutamate dehydrogenase (

Read et al., 2004) or β-giardin (

Lalle et al., 2005) genes, repectively.

G. intestinalis rDNA is present in the genome as approximately 60-130 repeated structures (

Boothroyd et al., 1987;

Sil et al., 1998). As in other eukaryotes, each unit of repeated structure is, formed by a small subunit (SSU), a 5.8S, and a large subunit (LSU) rDNA divided by 2 internal nontranscribing spacers (ITS). Intergenic spacers (IGS) are arranged between each unit repeatedly (

Healey et al., 1990). Since rDNA has multiple gene copies in all organisms, it is a suitable target for PCR amplification (

Waters and McCutchan, 1990). DNA sequences evolve rapidly in IGS and ITS, which are a part of the repeated structures in rDNA (

Hillis and Davis, 1986;

Hillis and Dixon, 1991). The sequences have been used to compare the differences between species in several protozoans (

Cupolillo et al., 1995;

Dietrich et al., 1990;

Didier et al., 1995). The length of ITS of

G. intestinalis, however, is very short (approximately 50 bp) and thus it is difficult to generate sufficient information for comparing isolates or strains.

Hence, we attempted the detection of G. intestinalis and determinination of its genotype simultaneously by PCR and nucleotide sequencing of the IGS region in rDNA of G. intestinalis isolates recovered from humans and other animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Giardia isolates

The cysts were obtained from the feces of 9 people infected with

G. intestinalis - 5 Chinese, 2 Laotians, and 2 Koreans. The K1 isolate originally obtained from a Korean cyst passer (

Park et al., 1999) and the WB and GS strains from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Maryland, USA) were cultured in the laboratory; thus, trophozoites were used.

Giardia cysts were isolated from dogs admitted to animal hospitals in Seoul, and field mice (

Apodemus agrarius) caught in Paju, Gyonggi-do (Province), Korea. Their cysts were isolated by the sucrose density gradient centrifugation method (

Table 1) (

Bingham and Meyer, 1979).

Genomic DNA of

G. intestinalis isolates was extracted. Cultured trophozoites, and the cysts obtained from the feces of hosts underwent 5 cycles of freezethawing using liquid nitrogen, and were treated with lysis buffer (1% SDS, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) containing proteinase K. Genomic DNA was extracted using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol and chloroform, and treated with RNase. To amplify the rDNA containing the IGS by PCR, 2 primers (GLF and GSR) specific to the 3' end of LSU rDNA and the 5' end of SSU rDNA were used (

Table 2). The PCR reaction solution was prepared with 10% glycerol, 0.01% gelatin, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 0.4 pmol of primers, and 10× PCR buffer (75 mM Tris-Cl (pH 9.0), 2.5 mM MgCl

2, 15 mM (NH

4)

2SO

4, 0.1 mg/ml BSA).

G. intestinalis genomic DNA and 0.5 units of

Taq DNA polymerase (SolGent Co, Daejeon, Korea) were added. For the PCR procedures, pre-denaturation was performed at 94℃ for 5 min. Then, denaturation was performed at 94℃ for 30 sec, annealing was performed at 56℃ for 30 sec, extension was performed at 72℃ for 5 min, and the procedure was repeated 30 times. Elongation was performed at 72℃ for 1.5 min finally.

Amplified PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and separated from the agarose gel using an UltraClean™ 15 DNA Purification kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Solana Beach, California, USA), and cloned into a pGEM® T-Easy vector (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). First, the nucleotide sequence near the portion of SP6 and T7 primer was determined. Additionally, by designing internal primers, the remaining portion of the nucleotide sequences was also determined. DNA sequences were analyzed by the dideoxy nucleotide chain termination method using a SEQ × 4 automatic DNA sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada).

Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the IGS and designing of primers

Nucleotide sequences of the IGS region of

G. intestinalis isolates were analyzed by multiple alignment analysis using the Clustal X program, and phylogenetic analysis was performed using the PAUP

* (version 4.0) program. The nucleotide sequence of

G. intestinalis rDNA (GenBank accession no. X52949) retrieved from the GenBank was compared with the nucleotide of the rDNA of human (GenBank accession no. U13369) and bacteria (GenBank accession no. J01859) using the Clustal X program. The primers specific to LSU and SSU rDNA of G. intestinalis were designed and termed GLF and GSR (

Table 2). In addition, the nucleotide sequence of the IGS of

G. intestinalis isolates was analyzed by multiple alignment and phylogenetic analysis using the Clustal X and PAUP

*. Then, the PCR primers were designed to react specifically to 3 assemblages (A1, A2, and B) of

G. intestinalis, termed GA1F, GA2F, GBF, and GABR (

Table 2).

IGS-PCR using assemblage A1-, A2-, and B-specific primers were applied to the genomic DNA of 12 G. intestinalis isolates. The genomic DNA of WB, K1, and GS isolates were used as positive controls. The genomic DNA of other protozoans, Entamoeba histolytica and Trichomonas vaginalis, as well as the bacteria Vibrio vulnificus and Escherichia coli were used. In addition, the specificity of IGS-PCR was examined by PCR using Giardia isolates from dogs and field mice. The genomic DNA was extracted from the cysts or cultured trophozoites using SDS lysis methods. The concentration of PCR amplification solution was prepared as described above for amplification of the rDNA region containing the IGS. The procedure was performed similarly, except that the annealing procedure was adjusted to 53℃ for 30 sec, taking into consideration the Tm value of the primers. The reaction products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel.

Sensitivity of IGS-PCR

The minimum amount of genomic DNA of G. intestinalis that could be detected by IGS-PCR was examined using the genomic DNA. The concentration of extracted DNA was determined by reading the absorbance at 260 nm. Genomic DNA was serially diluted to the final concentrations in the PCR solution from 100 ng to 0.1 pg by 10-fold dilutions and PCR was performed. The concentration of the PCR solution was prepared identically as described above. Reaction products were electrophoresed.

RESULTS

PCR amplification and cloning of IGS

By applying the primers GLF and GSR, which are specific to the 3' end of LSU rDNA and the 5' end of SSU rDNA, the rDNA sequences containing the IGS were amplified by PCR from 12 G. intestinalis isolates. From WB, K1, K2, K-L, CA9, CA13, CA14, and CA18 isolates, approximately 1.9 Kbp PCR products were amplified, and from GS, CA17, RD25, and RD37 isolates, 2.1 Kbp amplification products were detected. The amplification products of each IGS were cloned into the pGEM T-easy vector and treated with the restriction enzyme EcoR I, and then the cloning of the amplification products were confirmed.

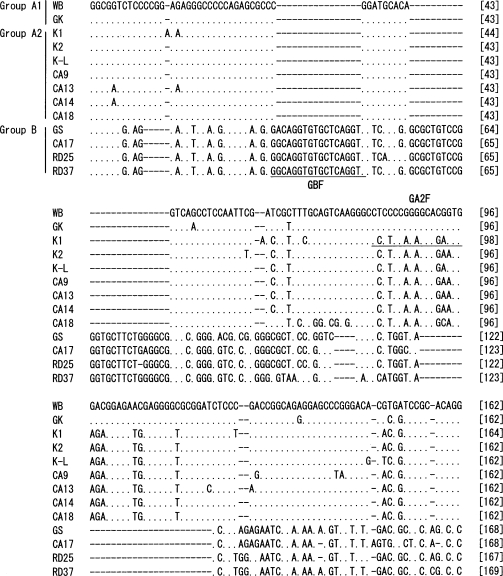

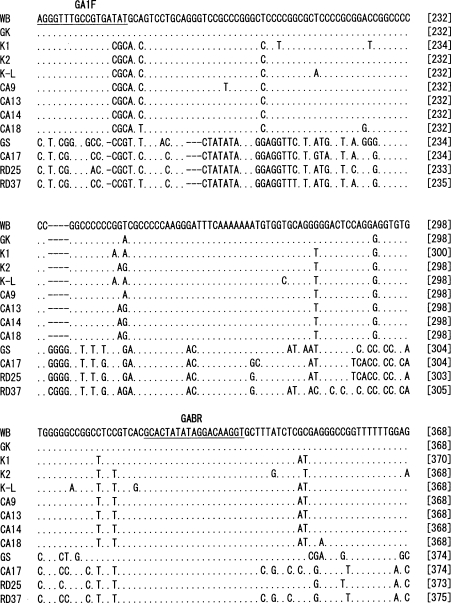

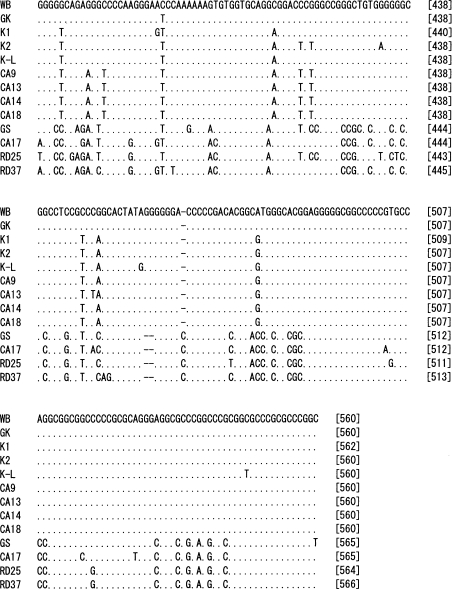

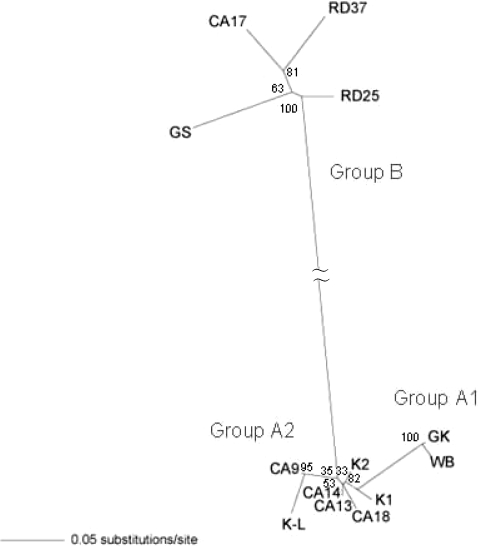

Nucleotide sequencing and analysis of IGS

The nucleotide sequences of 560 bp from the 3' end of IGS of each of the 12

G. intestinalis isolates were determined (

Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analysis was performed including the nucleotide sequence of GK strain, in which the IGS sequence was determined previously. The results showed that the genotype of 13

G. intestinalis isolates could be classified into the 3 different assemblages, A1, A2, and B (

Figs. 1,

2). In the IGS of assemblages A and B, besides the area with an evident deletion, 24% difference was detected among a 350 bp region near the 3' end. Assemblages A1 and A2 showed 0.06% difference among 560 bp. In the IGS of

G. intestinalis belonging to assemblages A (A1 and A2) and B, from the 3' end in the 5' direction, it was determined that the variation frequency of nucleotide sequence was high, and the nucleotide sequence specific to each assemblage was present. Thus, PCR primers that could be used to distinguish between genotypes were designed (

Table 2). The Korean isolates K1, K2, and K-L belonged to assemblage A2, and the Laotian isolates RD25 and RD37 belonged to assemblage B. The Chinese isolate CA17 belonged to assemblage B, and the other 4 Chinese isolates belonged to A2 (

Figs. 2,

3).

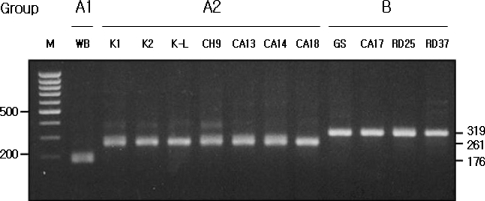

IGS-PCR using specific pairs of primers - GA1F and GABR, GA2F and GABR, or GBF and GABR - for assemblages A1, A2, and B, respectively, was applied to 12

G. intestinalis isolates. The pattern of PCR amplification with

G. intestinalis isolates was very similar to the assemblages determined by using the Clustal X and PAUP

* programs as described above. The length of amplification products were 176 bp for assemblage A1, 261 bp for assemblage A2, and 319 bp for assemblage B (

Fig. 3).

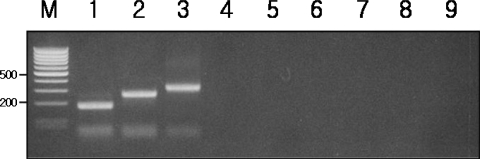

IGS-PCR was applied to the genomic DNA of

G. intestinalis WB, K1, and GS isolates,

Giardia isolates from dogs,

E. histolytica,

T. vaginalis,

V. vulnificus, and

E. coli. The results showed that besides

G. intestinalis, IGS-PCR did not show any amplification products with other protozoans including

Giardia isolates from other animals or bacteria indicating high specificity (

Fig. 4).

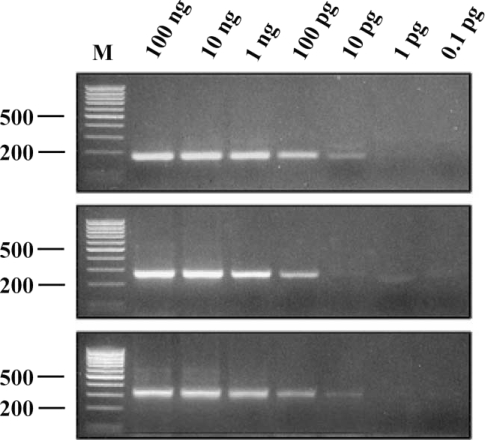

The minimum amount of

G. intestinalis DNA that could be detected by IGS-PCR was determined. Genomic DNA of WB, K1, and GS isolates were used as templates. In PCR performed with the genomic DNA of the K1 isolate, PCR product was detectable with 100 pg of template DNA, and in PCR using the genomic DNA of WB or GS isolates, 10 pg of template DNA was enough to produce PCR products (

Fig. 5). Thus, the IGS-PCR was reasonably sensitive to detect

G. intestinalis and effective in determining the genotyping simultaneously.

DISCUSSION

G. intestinalis isolates obtained from Koreans, Chinese, and Laotians were compared based on the nucleotide sequence of the IGS in this study, and the results showed that the 3 Korean isolates belonged to assemblage A, Laotian isolates belonged to assemblage B, and Chinese isolates were split between assemblages A and B. According to previous studies on the comparison of

G. intestinalis isolates obtained from humans and dogs using the nucleotide sequence of SSU rDNA,

G. intestinalis isolates in assemblage B from humans form phylogenetically closer relationship with

G. intestinalis from animals (

Yong et al., 2000), whereas subgroup A2 isolates were only found in humans (

Monis et al., 1996,

1998). Based on our data in this study, all Korean isolates belong to sub group A2. It was difficult to conclude, however, that zoonotic infection may occur more readily in any group of people because we examined only a small number of isolates and both assemblages A and B isolates have been recovered from broad range of hosts (

Monis et al., 1998). The distribution of each genotype differs according to the geographic locations or studies. The predominance of assemblage A was reported in a study in Korea (

Yong et al., 2000) and in Mexico (

Ponce-Macotela et al., 2002). Several studies performed in India, Peru, and the United Kingdom showed that assemblage B was responsible for more human infections than assemblage A (

Sulaiman et al., 2004). To get a more definite conclusion, further studies using a sufficient number of

G. intestinalis isolates must be performed.

Determining

G. intestinalis genotypes using the primers designed to be specific to each assemblage, the sensitivity of IGS-PCR was assessed in this study. The results showed that as little as 10 pg of

G. intestinalis genomic DNA was detectable. Previous studies reported the genomic DNA of a

G. intestinalis trophozoite to have a mass of 0.144 pg (

Erlandsen and Rasch, 1994). Therefore, IGS-PCR could detect as few as 100 trophozoites of

G. intestinalis. However,

G. intestinalis isolated from hosts are usually cysts. Since the cyst is resistant to various environmental stresses, it is difficult to disrupt cysts so that their genetic material can be released in vitro. When applied to the natural samples, the sensitivity of IGS-PCR is expected to be lower than the experimental detection performed using the genomic DNA extracted from trophozoites. Hence, effective isolation and lysis method of cysts from stool samples and purification of genetic materials are needed to obtain the result with a higher sensitivity.

With regard to the study on the genotype of

G. intestinalis, it was initiated by zymodeme analysis using several metabolic enzymes (

Andrews et al., 1989). Subsequently, various molecular biological methods were used, such as PCR with restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and the comparison of the nucleotide sequences of specific genes. Various loci including triose phosphate isomerase (

tpi) (

Amar et al., 2002;

Monis et al., 1999;

Sulaiman et al., 2004), glutamate dehydrogenase (

gdh) (

Homan et al., 1998;

Monis et al., 1996;

Read et al., 2004), β-giardin (

Caccio et al., 2002;

Lalle et al., 2005) and GLORF-C4 (

Yong et al., 2002) were used in the genotyping of

G. intestinalis at the molecular level.

Based on our results, IGS showed relatively more variations between each assemblage than

tpi genes (

Amar et al., 2002). To amplify IGS region with PCR, the primers (GLF and GSR) specific to LSU and SSU rDNA were designed, and the results showed that in assemblage A, approximately 1.9 Kbp amplification products were detected; in assemblage B, approximately 2.1 Kbp amplification products were detected showing approximately 200 bp difference between assemblages A and B. Hence, without the determination of the DNA sequence of IGS, assemblages A and B were able to be distinguished by PCR only. The difference in nucleotide sequences between assemblages A and B was 24% in 350 bp from the 3' end in the 5' direction of IGS excluding the region with deletions in a total 560 bp of IGS. Between subgroups A1 and A2, the difference of their nucleotide sequences in a total 560 bp was 0.06%, which was relatively low. However, there are nucleotide sequences which could be used for distinguishing subgroups A1 from A2 by designing specific primers for PCR. Using the sequences we could develop PCR amplication method for genotyping at one time.

An unexpected finding of the difference between the gdh and 16S rDNA genotyping results for some of the same isolates was reported (

Read et al., 2004). However, no difference was found between IGS data and SSU-rDNA genotyping in the previous report (

Yong et al., 2000) although subgenotypes A1 and A2 were noticed in the present study.

Five different subgenotypes (WA1 to WA5) in assemblage A, and 10 subgenotypes (WB1 to WB10) in assemblage B to reflect intragenotypic variations were reported, and 11 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in assemblage A and 26 SNPs in assemblage B were also seen in

Giardia isolated from raw urban wastewater in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S.A. (

Sulaiman et al., 2004). They speculated that subgenotype WA1 of assemblage A is more infectious to humans since 111 out of 131 samples belonged to assemblage A in their study. Another study identified 8 subgenotypes within assemblage A and 6 subgenotypes in assemblage B using β-giardin gene (

Lalle et al., 2005). In their results, 5 subgenotypes were found to be associated with infections of humans, of dogs and of calves supporting zoonotic infections.

The IGS-PCR method, using the primers designed specific to each assemblage, can detect G. intestinalis in the samples and determine the genotypes rapidly and accurately, being a very efficient method. The IGSPCR method established in this study would be useful for further investigations, such as epidemiological studies on G. intestinalis and correlation of the genotypes and clinical symptoms.

Notes

-

This work was supported by a research grant for development of Health and Medical Technology (01-PJ1-PG3-20200-0084), Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea.

References

Fig. 1Nucleotide sequence alignment of 3' part of the IGS from 13 G. intestinalis isolates. The abbreviations with initial letters CA, K and RD mean Chinese, Korean and Laotian, respectively. GK (GenBank accession no. X52949) nucleotide sequence was retrieved from the EMBL database. WB and GS were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. The dots indicate identical nucleotides and the hyphens indicate base deletions. Underlines show the position of the primer sequences for selective amplification of each assemblage.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Fig. 2Phylogenetic relationship between the 3 G. intestinalis IGS assemblages determined by neighbor joining method. The results showed that the genotype of 13 G. intestinalis isolates could be classified into the 3 different assemblages, A1, A2, and B.

Fig. 3Assemblage specificity of IGS-PCR. The 176 bp, 261 bp and 319 bp amplified products were specifically shown in the assemblage A1, A2 and B lane, respectively. Lane M represents 100 bp ladder from MBI Fermentas. The 500 bp and 200 bp bands were shown.

Fig. 4Specificity of IGS-PCR in recognizing genomic DNAs of other bacteria, protozoa, and non-human Giardia isolates. Lane M, 100 bp ladder from MBI Fermentas. The 500 bp and 200 bp bands were shown. Lane 1-3, G. intestinalis isolates WB, K1, GS; Lane 4, E. coli DH5α; Lane 5, V. vulnificus; Lane 6, E. histolytica; Lane 7, T. vaginalis; Lane 8-9, dog Giardia isolates GD1, GD2; IGS-PCR did not show any amplification products with other bacteria or protozoans including Giardia isolates from other animals.

Fig. 5Sensitivity of IGS-PCR. PCR product obtained using different amount of genomic DNA of WB (top), K1 (middle) and GS (bottom) isolate. PCR product was detectable with 100 pg of template DNA of K1 isolate, and using the DNA of WB or GS isolates, 10 pg of template DNA was enough to produce PCR products. Lane M represents 100 bp ladder from MBI Fermentas. The 500 bp and 200 bp bands were shown.

Table 1.

Giardia isolates examined in this study

Table 1.

|

Isolates |

Geographic origin |

Host |

Nature of sample |

Reference |

|

WB |

Afghanistan |

Human |

Trophozoites |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

GK |

Australia |

Human |

Unknowna)

|

(Healey et al., 1990) |

|

GS |

USA |

Human |

Trophozoites |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

K1 |

Korea, Seoul |

Human |

Trophozoites |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

K2 |

Korea, Seoul |

Human |

Cysts |

This study |

|

K-L |

Korea, Seoul |

Human |

Cysts |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

CA9 |

China, Anhui |

Human |

Cysts |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

CA13 |

China, Anhui |

Human |

Cysts |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

CA14 |

China, Anhui |

Human |

Cysts |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

CA17 |

China, Anhui |

Human |

Cysts |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

CA18 |

China, Anhui |

Human |

Cysts |

This study |

|

RD25 |

Laos, Saravane |

Human |

Cysts |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

RD37 |

Laos, Saravane |

Human |

Cysts |

(Yong et al., 2002) |

|

GD1 |

Korea, Seoul |

Dog |

Cysts |

This study |

|

GD2 |

Korea, Seoul |

Dog |

Cysts |

This study |

|

GM |

Korea, Pajoo |

Field mouse |

Cysts |

This study |

Table 2.The primers used for the PCR amplification in this study. GLF and GSR primers were used for amplication of the whole IGS region, and other 4 primers were used for selective amplication of each assemblage, respectively

Table 2.

|

Function |

Name |

Nucleotide sequence |

|

Upstream primer for IGS region |

GLF |

5´-GACCGTCGTGAGACAGGTTAG-3´ |

|

Downstream primer for IGS region |

GSR |

5´-CCTGCTGCCGTCCTTGGATG-3´ |

|

Upstream primer for group A1 |

GA1F |

5´-GGTTTGCCGTGATATGCA-3´ |

|

Upstream primer for group A2 |

GA2F |

5´-CCCTCCAGAGCAGMRTGAGA-3´ |

|

Upstream primer for group B |

GBF |

5´-GRCAGGTGTGCTCAGGTG-3´ |

|

Downstream primer for group A & B |

GABR |

5´-AGCACCTTGTCCTATAYAGT-3´ |